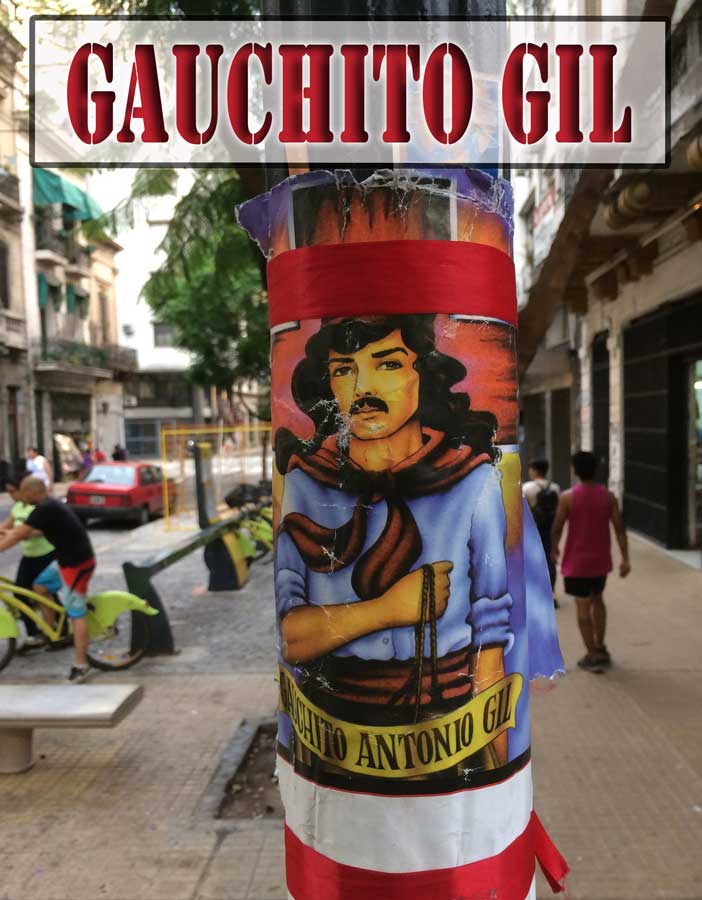

In the bleak part of the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Chacarita, in a tree-lined plaza just outside the country’s largest cemetery, a cluster of bright red clearly marks the location of a Gauchito Gil shrine.

←continued from Gauchito Gil—Argentina’s Gaucho Saint

A pair of old women come to place flowers in front of the glass-encased statuette of Gil.

A youth in his late teens sits drinking wine from a cardboard carton, talking solemnly with his girlfriend. Every few minutes she limps over to the shrine to relight a candle, revealing a tattoo of the gaucho on her calf.

A man cleans the glass front of the shrine and scrapes away the red wax that is forming a puddle on the ground. His name is Juan, and he is in charge of keeping the shrine neat, he explains.

“People come here because Gauchito Gil has a gift,” he explains.

“He cures people and he protects them. They come here to ask for his help.”

Asked why people believe in Gil, he is frank.

“Because he is miraculous. They see evidence of what he does and they have to believe.

“Truck drivers ask for safe passage; it’s even common for robbers to ask him for help before they go thieving.

“The important thing is that if you ask for something, you do something for him in return.”

Fabian Amarillo, who has come to the shrine with his wife and small children, doesn’t entirely agree.

“I don’t ask for anything from the Gaucho,” he says.

“He is a friend. He’s always by my side. He gives me help without me asking for it. I say hello to him, and pay tribute to him with little shrines in my house. I have him here on my chest.”

Fabian reveals a large tattoo of Gil covering his chest and stomach.

“I don’t believe he helps the thieves when they ask him. He helps people to move forward with their lives. He helped me to move forward.”

Latin America’s Pagan Saints

In a strongly Catholic country, it may seem unusual that a figure not endorsed by the church could be so widely revered as a Saint.

Firstly, it is worth noting that many Catholics don’t buy into the Gauchito Gil cult at all, sticking to the official church line.

There are even doubts as to whether Antonio Gil was a real person, as there is little historical evidence to support the story.

But the fact that so many choose to believe in his powers is not so surprising when one considers that in Argentina, and Latin America in general, Gauchito Gil is just one of many folk saints that are worshiped by large sections of the populace without regard to the official church position.

Niño Fidencio, for example, is a healing folk saint who commands a huge following in Mexico and southern Texas, performing his miracles through earthly mediums.

The one pagan saint in Argentina to rival Gauchito Gil for popularity is Difunta Correa, whose cult emerged several decades earlier in the province of San Juan.

Difunta Correa’s story is another of resilience in the face of corrupt authority.

When her sick husband was forcibly recruited into the army, she set off after the troops with her infant baby in order to save him, following their tracks through the desert.

She was overcome by the elements, however, and died, but miraculously her baby survived for several days by feeding on her still-full breast, until he was found by roaming gauchos.

Frank Graziano, Professor of Hispanic studies at Connecticut College and author of ‘Cultures of Devotion: Folk Saints of Spanish America,‘ (partner link) explains the three main reasons why so many people become devotees:

“They believe that folk saints are more miraculous than canonized saints (folk saints get the job done, sometimes after request to Catholic saints fail); freedom of devotion, which is to say without the mediation, restrictions, and cost of priests; and what they call ‘lo nuestro,’ meaning that the saint is ‘one of us,’ part of their community, and therefore has shared their social situation and understands their requests.

Remember too that folk saints supplement Catholicism rather than replacing it,” he says.

In a way, the anti-authoritarian image of Antonio Gil makes it irrelevant to his followers whether his sainthood is acknowledged by the Church or not.

Like the other folk saints, Gauchito Gil’s popularity stems in part from his image as a rebel who was killed by — but never subservient to — the powers that be.

It’s clear Gil belongs to the people, not the church or the state.

He is as relevant to farmers and peasants in the poor provinces who feel ignored by the centralized government as he is to the residents of the Buenos Aires slums.

Those who live in shanty towns reference him in Hip Hop and Cumbia songs, and also feel like they too are no part of the establishment.

“We believe in many lies in this world, we even believe in politicians,” reasons Fabian at the shrine in Chacarita.

“What does it matter to me what they say about Gauchito Gil. I see what he does every day with my own eyes. My faith is limitless – I feel it in my soul.”

—by Dan Colasimone