Lunfardo is a jargon of about 5,000 words that emerged among the lower classes in Buenos Aires in the second half of the 19th century.

The slang first grew out of cocoliche, a pidgin used by immigrants during the first wave of immigration to Argentina.

The Argentine Creole was born out of a need to communicate among people who had different regional dialects of their respective languages, mostly Spanish and Italian.

Lunfardo’s Criminal Roots

Lunfardo is closely tied with the tango culture and has roots in the criminal underbelly.

Much of the dialect was developed in the prisons as a way for inmates to speak among themselves without being understood by guards.

Lunfardo later incorporated smatterings of words from other immigrant groups, the gauchos, or cowboys, of Argentina, the indigenous of the country and Africans, both before and after emancipation.

Lunfardo is employed in the River Plate region and although it has permeated Argentine culture, the vocabulary is not widely understood in other Spanish-speaking countries with the exception of Uruguay.

Italy’s Influence on Lunfardo

In addition to Italian words that have been imported directly into the Argentine lingo, such as, ciao (spelled ‘chau’ in Argentina), to bid farewell, there are a plethora of Lunfardo words with easily traceable Italian roots.

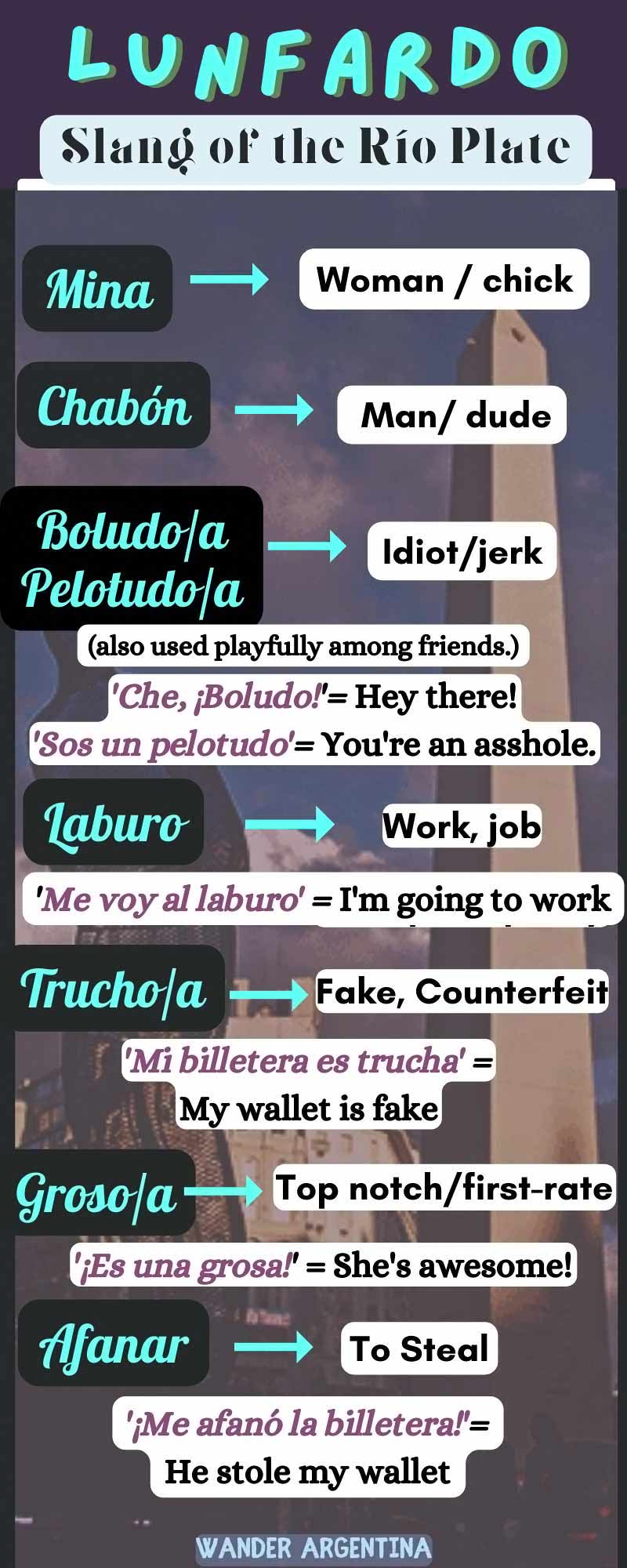

The word mina, commonly used to refer to a woman, comes from the Italian word ‘femmina.’

The verb ‘laburar,’ meaning ‘to work’ and derived from the Italian word ‘lavorare,’ is frequently used in place of the verb trabajar.

Fiaca, used to describe a state of laziness, comes from the Italian word, ‘fiacco.’

Ñoquis: Not just a Pasta in Argentina

Similarly, ñoquis is the Argentine version of the Italian ‘gnocci.’

Besides describing the pasta dish that has become common to eat on the 29th of each month when money is tight, the term ‘noquis’ can also make reference to the size of genitalia.

Most commonly the word ‘ñoqui’ is used in its Lunfardo sense to refer to someone who gets paid for a job they don’t do.

In Argentina 55% of registered workers work for the government and its not a secret that many just show up and collect a check without actually working.

These state employees are called ñoquis, many people view these state employees as people who fade into the background of bureaucracy and sit around and drink yerba mate all day.

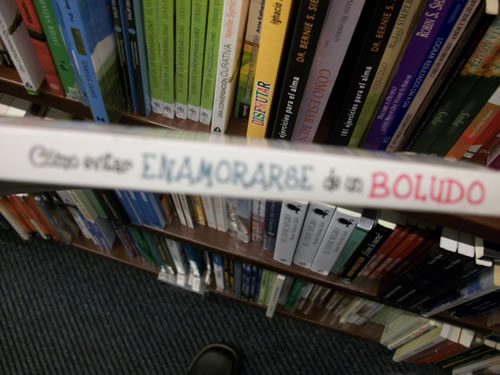

Argentina’s Most Common Insults: Boludo & Pelotudo

Another term almost as ubiquitous as ‘che,’ despite its rather impolite implications is the word boludo/a, used incessantly by teenagers, much to the torment of teachers and well-meaning parents.

Although referring to the size of someone’s testis — someone with genitalia so big it impedes their movement — today it takes on the meaning of ‘idiot’ or ‘jerk’ and is used by friends to playfully address each other or as an insult in a heated conversation.

‘Che, boludo‘ is such a common way to address someone, there is a book with that title.

The term boludo originates from the gauchos who fought against the Spanish in Argentina’s war for independence.

The Spanish soldiers were better armed, so Argentina’s gaucho soldiers had to get creative to defeat them. They used a hunting weapon called a boleador, rocks, or weighted balls tethered to either side of a rope.

By lancing the bolas (balls) when the Spanish cavalry charged them, those on the front lines could knock the horses down, dismounting the charging soldiers.

The second line of criollo soldiers followed, spearing the colonial soldiers once they were on the ground.

Originally a ‘boludo’ indicated someone brave, but in the political discourse of the time came to refer to someone stupid enough to risk their lives on the front lines.

Synonymous with boludo is the word pelotudo/a, although this word usually has harsher implications. References to genitalia are abundant in Lunfardo — boludo and pelotudo are just two examples.

Quilombo/ Bolonqui

African influences in Lunfardo can be heard with the use of quilombo, a heavily colloquial term that has found its way into everyday use.

Originally, a quilombo was a gathering place for slaves, and in some areas referred to a brothel, but over time the word took on a meaning more synonymous to a ‘total mess’ or ‘disaster.’

As with a lot of language in Argentina, the term quilombo is not exactly politically correct, but it persists.

In polite company, someone may use the term, ‘bolonqui‘ instead. Read on to find out why.

Chamuyo and Chamuyeros

Another word that sounds so pretty but can turn out ugly is chamuyo.

This can be innocent sweet talk from a guy trying to score with a girl or out-right scheming and scamming.

The verb for the word is chamuyar and a person who does it is called a chamuyero (or ‘chamuyera’ for a woman.)

A worker who talks about what a great job he’ll do while dollar signs are rolling in his eyes, an acquaintance who swears they’ll do a favor and then evades your phone calls, or a guy who swears he’ll love a girl forever and then abandons her after she’s knocked up –- all those scenarios fall within the chamuyero spectrum.

Word Mashups in Lunfardo: Vesre

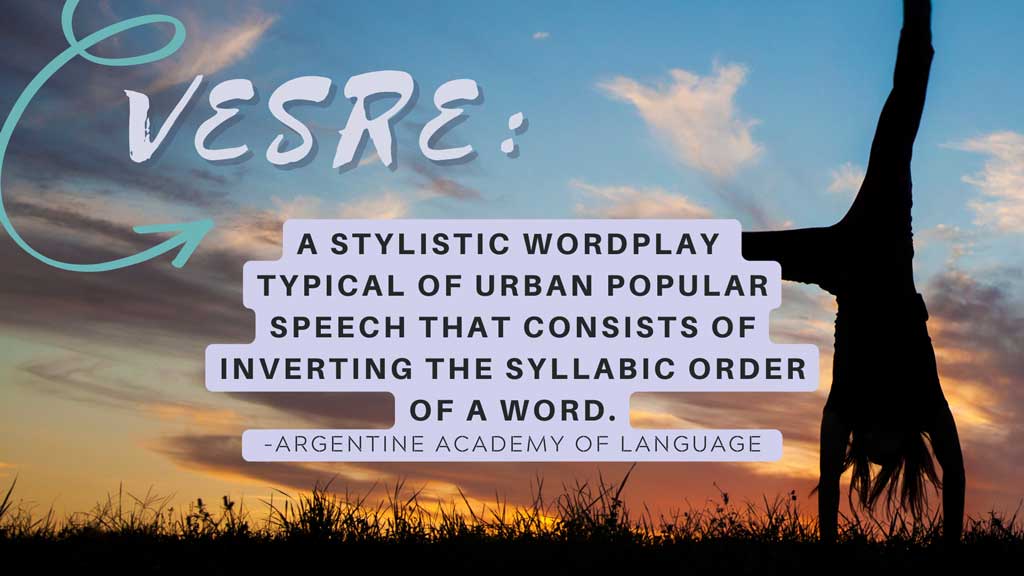

Fundamental to Lunfardo, and characteristic of the wordplay it is recognized for, is vesre.

Vesre is a feature of Lunfardo that can be likened to Pig Latin for adults. Words are formed by switching around the syllable of word, similar to the verlan of French.

An example is the word vesre itself – switch it up and it becomes revés, meaning ‘reverse.’

Suddenly the reason this slang is named vesre is no mystery. Thus in Lunfardo:

Aregentina Vesre Words

| VESRE | SPANISH | ENGLISH |

| ‘feca’→ | café | coffee |

| ‘jermu’→ | mujer | woman |

| ‘gomía‘→ | amigo | friend |

| ‘zapi’ → | pizza | pizza + Argentine pizza chain name |

| ‘gapar’ → | pagar | to pay |

| ‘ajoba’→ | abajo | down |

| ‘sope‘ → | peso | Argentine peso |

| ‘jovie‘ → | viejo | old (used for ‘dad’) |

| ‘ñoba‘ → | baño | bathroom |

| ‘dolobu‘ → | boludo | jerk/buddy (depending on context) |

| ‘gotán’ → | tango | tango, eg. musical group, Gotán Project |

Some other vesre terms, such as ‘bolonqui’ (quilombo) maintain their significance while others such as telo/hotel, take on a slightly different meaning when reversed.

A telo is a hotel for couples to escape to for a night or just a few hours specifically to have sex — useful to know in case a chamuyero invites you to one when you’re in a boliche (club).

Understanding Lunfardo is like understanding a riddle and may take some time.

Even those who have perfect Spanish skills have trouble following Lunfardo-laced conversations, especially when the colloquial banter includes vesre.

While Lunfardo adds a unique and sometimes plebeian flare to the already unique identity of Argentina, it also contributes a dynamic twist to everyday life.

Slang is constantly influencing speech and vesre makes the creation of new — although not official — words endless.

Although purists believe that a word cannot be considered Lunfardo unless tied to its tango or immigrant roots, Argentines are taking liberties with the vernacular, making it a challenge to ever really get a strong handle on the lingo — and that’s half the fun.

— by Jenna Frisch with Ande Wanderer

(← cont. from Argentinismos)

2 thoughts on “Lunfardo: The Dirty Slang of Buenos Aires”

Comments are closed.