Outside of Buenos Aires and in small pockets around the city, tango loses its supremacy on the dance scene in favor of Argentine folclore, folk music and dance from different regions around the country.

Unlike tango’s nocturnal sensuality, Argentina’s upbeat folklore evokes loud music, afternoon cheer and families enjoying the sunshine.

Argentina Folk: History and Roots

The name ‘folclore’ comes from the mid-19th century English word folklore. In Argentina, the term specifically refers to the popular regional music folklórica, folk songs and dances with indigenous, African and colonial origins.

For many years Argentina’s regional folk music and dances were not recorded or written down, and were unknown outside their own region.

This changed in the early 1900s when a musician known as the ‘patriarch of folklore’ named Andrés Chazaretta formed a group called the ‘Conjunto de Arte Nativo’ (the Collection of Native Art) and began recording folklóricos. He then performed them throughout the country on a 1906 tour.

Since then, folklore artists have gained prominence and popularity around the country and all the way to the capital.

Folklórica is strongly linked with both regional and national identity. This feeling peaked in the 1950s and 60s, when the country experienced a folklore revival referred to as the ‘boom del folclore.’

Renewed interest in Argentine folk music coincided with increased urbanization, as rural families brought their traditions into the cities while radio, television and cinema facilitated the spread of unique regional sounds and a political desire to emphasize a strong Argentine identity, instead of always adapting European traditions.

This national boom led to the 1960’s and 70’s movement called the ‘Movimiento del Nuevo Cancionero,’ or the New Singer Movement.

Headed up by musicians Mercedes Sosa, Armando Tejado Gomez, Toto Francia, Oscar Matus and others, the self-described ‘literary-musical’ movement sought to bring together the different types of popular Argentine music.

This bridged the divides between genres such as tango, folklore, and even national rock by combining different elements of each to create something new.

Folk Music During the Dirty War

During the Dirty War of 1976-83 the government repressed political, cultural and artistic expression, banning many popular folk songs because of their subversive lyrics in addition to ‘disappearing’ many intellectuals and artists.

Some of the most famous Northern folklore musicians of the 20th century such as Atahualpa Yupanqui, Los Hermanos Ábalos, Carlos Carabal, Cantores del Alba, Los Tucu Tucu, and the Manseros Santiagueños spent time in exile because of the censorship.

At a festival in January 1978, the folk musician Jorge Cafrune played a song requested by the audience, even though it wasn’t in the government’s ‘approved songs’ list.

“Even if it’s not in the authorized register,” he said at the time, “if the people request it, I am going to sing it..”

A short while later, Cafrune was killed in a hit-and-run accident while traveling by horseback.

Many believe he was assassinated by the military junta, who deemed him too famous for a public trial and imprisonment.

In 1979 the internationally famous singer Mercedes Sosa had her concert interrupted and was arrested on stage, along with her entire audience at a show in Mar del Plata.

She chose to flee the country after that incident along with many other folkloric artists who were frustrated by their inability to perform and feared for their lives.

In the early 1980s the dictatorship’s grip on the country slackened and many artists returned home.

A new generation was introduced to the genre, and to artists who had been unable to release their music in their own country for almost a decade.

Since then, folklore music has regained its standing as an essential part of the Argentine national identity.

Argentine Folk Dances

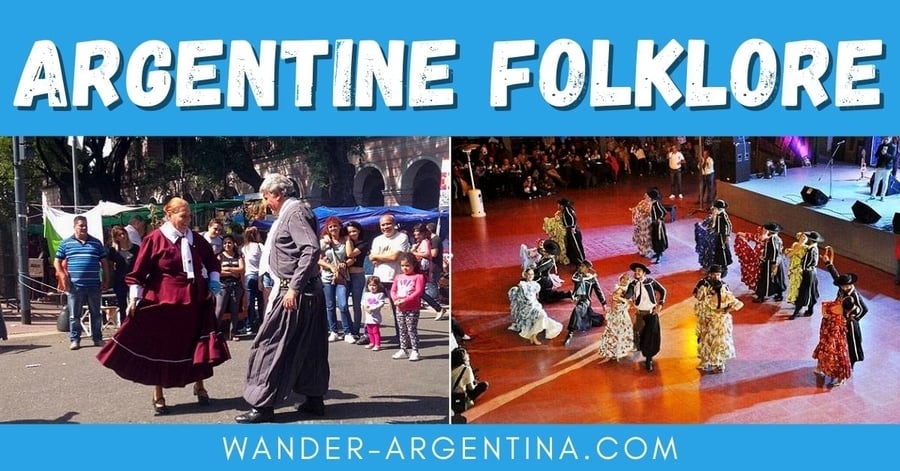

Argentina has a patchwork of traditional dances covering its large territory.

Among the many different types of Argentine folk music, the most well known in Buenos Aires are probably chacarera, chamame and zamba —not to be confused with the Brazilian samba.

Many other regional dances include el gato, yaraví, palotiro, bailecito, el escondid, pericón, carnavalito, malamba, cuecas, chaya, payada, and chamarrita.

Chacarera and zamba both originated in the northwest of the country, and their popularity radiated outwards from the 1930s onward, due to Argentines’ renewed interest in traditional dances and internal emigration towards the capital.

Chamamé, from the Littoral region, is a uniquely Argentine mix of Guarani and Eastern European music, merged with a African beats and sad lyrics typically accompanied by guitar, bass, and accordion.

Chamamé music has hints of polka and is danced in pairs. It is the closest thing Argentina has to the waltz, although it employs a 6/8 beat.

Chamarrita is a kindred song and dance, also from Argentina’s Mesopotamia region, which is believed to be related to a Portuguese song and dance of the same name.

Chacarera: A Favorite Folk Dance

The first recorded use of the name ‘Chacarera’ dates back the early 1900s. The music comes from a mix of African, indigenous and, to a lesser extent, colonial roots.

“Maybe on an international level Argentina is mostly represented by tango, but in Argentina you realize that Chacarera is national, it’s popular everywhere,” says Esteban de Monte, a folklore dance teacher living in Buenos Aires but originally from Santiago del Estero, the birthplace of chacarera.

One appeal for beginners is chacarera’s relative simplicity: unlike tango, chacarera is a choreographed dance, with only a few basic steps and variations that repeat several times.

Dancers form two lines, and partners stand facing each other. Partners move forward and back, in clockwise circles, and meet in the middle, always keeping their torsos turned towards each other and their eyes focused on those of their partner.

Adrian Bernal, a folklore dance instructor who gives classes at Buenos Aires’ dancehall La Catedral says, “Chacarera is danced separately, there is no physical contact. But you stay in contact with your partner through the energy you share with the other person. Dancing is communication.”

The lyrics to traditional chacarera songs often deal with similar themes: the beauty of nature, nostalgia for home, traveling through the countryside, and country life.

Many chacareras refer to the act of singing a chacarera within the lyrics of the song. The songs are sung in Spanish and Quechua and there are a few variations of the choreographed dance.

During the bridge, men perform a move called zapateo — zapato meaning shoe in Spanish — stomping the ground loudly and rhythmically. Meanwhile women do the zarandeo, twirling their long skirts while dancing in a small circle.

“The zapateo is like a floreo (flattery) that the man performs for the woman — an invitation,” Bernal explains.

“And the woman can choose to answer — or not — with a zarandeo because a zarandeo can be an insinuation, a response, or it can be a rejection. In the zamba this conversation is more noticeable. Zamba more than anything else is a dance between couples.”

‘Añoranzas'(Yearnings)– Lyrics of a chacarera by Julio Argentino Jerez:

Cuando salí de Santiago todo el camino lloré lloré

sin saber porqué pero yo les aseguro que

mi corazón es duro pero aquel día afloje.

Quisiera ser arbolito, ni muy grande ni muy chico

pa´ darle un poquito ´e sombra y a los cansados del camino

Cuando chacareras comienzo a cantar ¿Cual ha de ser..?

¿Cual ha de ser…? La chacarera del rancho, señor.

¡claro que si! !claro si, pues!

When I left Santiago I cried the whole way

without knowing why but I assure you that

my heart is tough but that day it went soft.

I would like to be a tree, not too big nor too small

To give a little bit of shade to the tired people on the road.

When I start to sing chacareras, which will it be?

Which will it be? The chacarera of the ranch, sir

Of course! Of course!

Zamba: The Swirling Scarves Dance

Couples dance Zamba while twirling scarves. The dance is also found in parts of Peru and Bolivia, and has many common elements with the cueca, the most well-known Chilean folk dance.

The name zamba comes from the colonial term ‘zambo,’ which refers to the offspring of Amerindians and Africans.

Zamba is native to the provinces of Tucumán and Santiago del Estero, provinces where there is still a small native Afro-Argentine population.

Zamba arrived in Argentina through two different routes. The ancestor of the dance is a Peruvian dance called zambacueca. It passed into Chile and became the cueca, which then arrived in the province of Mendoza, Argentina.

At the same time, the zambacueca also descended directly from Lima towards Jujuy.

The zambacueca is now called marinera in Peru; all three dances (marinera, cueca and zamba) remain similar, though stylistic and rhythmic changes now mark them as distinct types of music.

Along with the chacarera, the zamba is one of the most well-known Argentine folk dances. In 2007 was nominated to be named national dance of Argentina.

The most distinctive aspect of zamba is the handkerchief that the partners twirl in the air, inviting and teasing each other with their movements. It is widely considered the most romantic of Argentine folk dances.

“In Argentina, zamba is the expression of romance,” says Bernal. “It’s the symbol of sweetness, the gentleness of love that is sublime, tender, and sensitive. It’s a part of life.”

Zamba song lyrics intertwine love, sensuality, and nature. Like chacarera, zamba lyrics often refer to the act of singing or dancing zamba within the lyrics of the songs.

Folklore Instruments and Outfits

Being from the same region of the country, chacarera and zamba use similar instruments and dancers wear similar traditional clothing.

Women wear long, full skirts, necessary to perform an elegant zarandeo and men wear wide gaucho pants called bombachas that narrow at the ankle, heavy boots, shirts, wide-brimmed hats and scarves.

In addition to more common instruments such as the guitar, violin, and drums, chacarera and zamba also employ the bandoneón, a type of concertina that looks similar to an accordion and is often used in tango music.

Indigenous Andean instruments include the quena, a wooden flute and the charango, which resembles a small banjo. The trademark drum is the bombo legüero, made from a hollowed out tree trunk and animal skin, it has a deep boom that can be heard over long distances.

It is disputed where the origin of the word ‘legüero’ derives — different academics claims it has African, creole or indigenous roots. One good theory is that the name comes from the Quechua word legüi, a rope with balls at each end used to hunt and designed to catch animals by tangling in their legs.

Angélica — First Stanza of a Zamba by Roberto Cambaré:

Angélica, cuando te nombro me vuelve a la memoria, un valle…

pálida noche de abril y aquel pueblito de córdoba.

Te vi, no olvidaré

Un carnaval guitarra, bombo y violin,

agitando pañuelos te vi, cadencia al bailar,

airoso perfil

Angélica, when I say your name I remember a valley…

a pale night in April and that small village in Cordoba.

I saw you, I won’t forget

A carnival guitar, bombo and violin

Moving handkerchiefs I saw you, dancing with rhythm,

graceful profile.

Folklore Dancers and Musicians

Even if Argentine folklore is not as visible to tourists as tango, the vast majority of Argentines have tried dancing it, if only back in their school days.

“On national holidays, like the 25 of May or July 9th (Independence Day), they teach you the history in school, and you learn the traditional music and dances. It’s not mandatory, but everyone participates,” says Melissa Bafico, a med student in Buenos Aires.

Few porteños continue to dance folklore after their school years, but the dances are common in the countryside, especially in the northern provinces.

And even in Buenos Aires, die-hard folklore dancers will don traditional costumes before setting out to dance at their favorite folkloric peña (folklore venue).

Where to See Argentina’s Folklore

For those who want to catch a show or practice their moves, there are several places in Buenos Aires where folklore is alive and well, and all sorts of people — wearing everything from traditional garb to jeans and t-shirts — attend to dance and listen to music.

The most reliable place to see and dance Argentine Folklore is the Mataderos Fair every Sunday.

There are also many peñas in town, some of which have been around for years, others that pop up and disappear again after only a few months.

Spanish speakers can find more info on live performances and peñas in Buenos Aires on the Folklore Club homepage or by joining the Facebook group ‘Los Peñeros de los Sabados.’

Tango temple La Catedral also currently offers folklore dance classes on Saturday afternoons from 5 to 7 p.m., for those interested in learning the moves — just email or call in advance to confirm.

Those traveling outside the capital to the provinces of Salta, Tucumán, Jujuy and Santiago de Estero will have many opportunities to see zamba, chacarera and other folkloric dances.

For a more formal sit down event, the tango shows in Buenos Aires all contain a folk music and dance segment. Another excursion that provides an opportunity to see live folklore (as well as ride horses and eat a delicious asado lunch) is on a day trip to an estancia outside Buenos Aires.

National Folklore Festival of Cosquín

The National Folklore Festival of Cosquín, takes place near Cordoba city in the town of Cosquín during the last nine days of January.

The festival began in 1961 and is now one of the most important dance festivals in Latin America. It’s a chance for visitors to see the beautiful Punilla Valley and see the breadth of this under-appreciated national music and dance.

The festival takes place during National Folklore Week and is televised around the country.

Those not able to make it to Cosquín might still find smaller folklore gatherings in other areas of the country during National Folklore Week.

The Idiosyncrasy of a People

Folklore is an important part of Argentina’s culture often overlooked on the world stage.

Folklore musician Duende Garnica says, “Folklore is the idiosyncrasy of a people — its culture, customs, food, dances, are mapped out inside the music and the poetry of the dance.

For this reason folklore is crucial in order to know where we come from and where we are going.”

-Sam Harrison

→ Check out the city’s most renowned tango shows, all of which include a folklore and folk dancing segment as part of the show.

→ To see Argentine Folk Music and Dancing in Buenos Aires, book our tour of the Mataderos Fair, where you’ll enjoy the song and dance and likely meet some of Argentina’s most renown folk artists.

→ Read about Carnival music, dance and celebrations in Buenos Aires