In the ragged history of Argentine politics one phenomenon which remains constant amongst all the turmoil -– the figure of the all-powerful Latin American leader known as the caudillo.

Ex-president, Néstor Kirchner was one of many of a long line of charismatic and single-minded leaders who have shaped Argentina’s history since independence.

From Manuel Rosas to Juan Domingo Perón to Néstor Kirchner, these strongmen have used charisma and cunning to lord over the multitudes, crush those who oppose them and reap that which nourishes them — power.

Not unique to Argentina, they have time and again risen across Latin American, representing the political embodiment of Latino machismo.

Traditionally, the caudillo is a leader who is ruthless, popular, brave, reckless but often calculating, unquestionably masculine and willing to use violence to achieve his goals.

Augustus Caesar, Benito Mussolini, General Franco, Fidel Castro, Hugo Chávez and Mexico’s Antonio López de Santa Anna shared many of the characteristics of the Argentine caudillos.

In order for a caudillo to emerge, tinderbox conditions must exist.

There has to be a vacuum of power or deep unrest, meaning that somebody with a magnetic personality shouting magical promises is able to ride a wave of popular support, often winning his ruling clout in a short amount of time.

Political leanings are of secondary importance once a populist personality cult is formed.

History demonstrates that many of these nationalistic leaders display mixed and often contradictory dogmas, ranging from the extreme left to the extreme right.

The Emergence of the Modern Caudillo

While caudillos throughout history have had much in common, the role has gradually evolved to fit the political climate of the times in which they lived and ruled.

Early editions of caudillos were little more than barbaric warlords, dependent on a feudal covenant of protection and devotion of their underlings and a strong military force to consolidate their power.

In the mid-twentieth century, various dictators throughout the Latin world maintained their command through a combination of military strength, popular support, propaganda and an insidious and tactical elimination of their enemies.

The contemporary caudillos is a more political beast.

He doesn’t rely on brutal force such as his predecessors, but a certain ruthlessness remains, as well as a more cunning use of threat, intimidation and manipulation of the media to repress opponents.

Often they gain power by democratic means, and then go to extreme measures to maintain it, utilizing propaganda to manufacture an image of wild popularity.

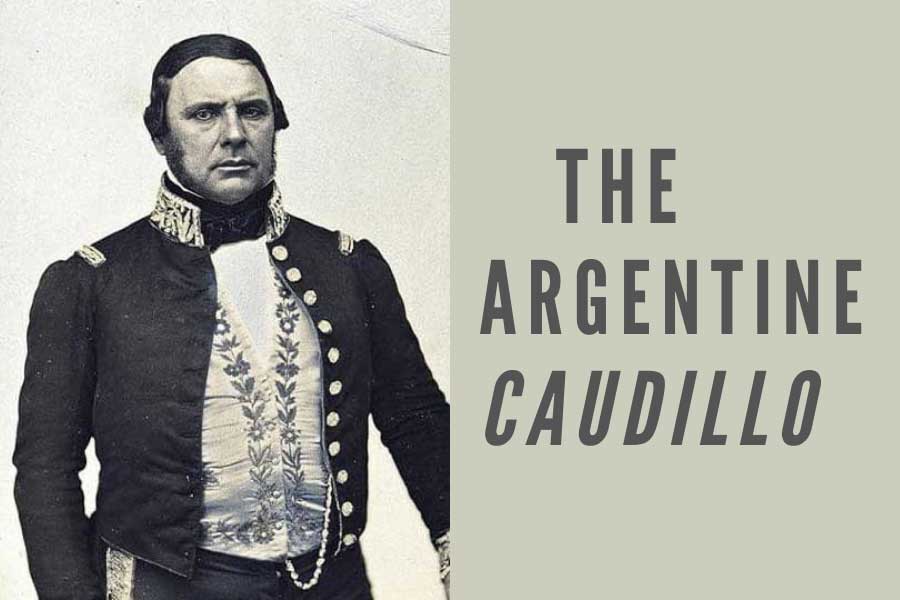

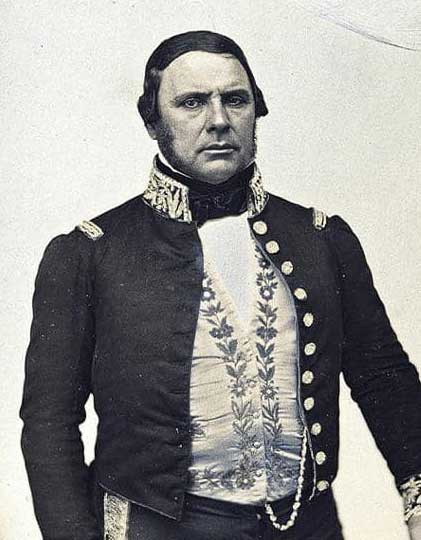

Manuel Rosas, the Prototypical Argentine Caudillo

“Rosas — fake, cold-hearted, calculating spirit who commits evil without passion and slowly orchestrates despotism with all the intelligence of a Machiavelli.”

—Former president José Sarmiento describing Juan Manuel de Rosas, the original great Argentine caudillo, in his historical novel, Facundo.

When Buenos Aires declared its independence from the Viceroy in 1810, as a response to the overthrow of King Charles IV in Spain, it set in motion a period of great instability and a disintegration of traditional power bases, especially in the outlying municipalities.

Civil war raged, with the central issue of the time being whether to unite the provinces under a federal system (Federalism) or allow them their individual freedoms to govern as they wished (Unitarianism).

Where no central authority existed, large landowners grew in power. They offered work and sanctuary for many men.

The age of the wandering gaucho was coming to an end, and many of these fierce nomad cowboys joined the provincial militias of men such as Buenos Aires’ Colonel Manuel Dorrego, Salta’s Martin Güemes, San Juan’s Angel Peñalosa, La Rioja’s Juan Facundo Quiroga and the aforementioned Juan Manuel de Rosas.

Their attempts to instill governance in the capital of Buenos Aires largely failed.

When two northern Unitarian caudillos moved their forces south with their eyes on the capital, the most powerful strongman of the time, Rosas, was entrusted to take command of the military of Buenos Aires and a unified force of private armies to confront the advancing threat.

He did so with aplomb, and consolidated his power as the popular governor of Buenos Aires.

From there, Rosas went from strength to strength, ruling a more unified Argentina for more than 20 years with dictatorial menace.

He provided the template for future caudillos –- the people were blessed with a much more stable country with a strong military to ward off invasions, but paid the price with the loss of many basic freedoms.

Rosas ruled through fear, violence and intimidation, backed by his loyal armed forces and secret police, the mazorcas, until he was eventually overthrown and exiled to England in 1852.

Manuel Rosas died as a farmer in Southampton, England in 1877.

History Repeating in Argentine Politics

The regional warlords of the early 1800’s were a precursor to later, modern versions of the caudillo. As Argentina developed a more structured political system, power-seeking strongmen were forced to adjust their strategies.

The likes of Justo José de Urquiza and Ricardo López Jordán increased their power through political channels in the mid-19th century, though it was through military might that they first established their credentials, and it was that strength of force that determined their success.

The one time allies eventually became bitter enemies.

Urquiza ruled the country as president from 1854-60, creating a national constitution for the first time.

López Jordán could never muster an army great enough to overthrow his nemesis, despite numerous attempts.

Even since those heady days, the trend for Argentine leaders to rise up like messiah-like and seize control of the country continues.

A vicious cycle of short-sighted leadership in the country fuels the repetition of earlier mistakes.

Charismatic leaders emerge riding a wave of popularity by promising near-instant solutions to a myriad of problems.

When institutional weakness and lack of foresight ensure that things inevitably go severely array, there is a strong backlash and a new savior emerges, promising to fix all the problems of the last.

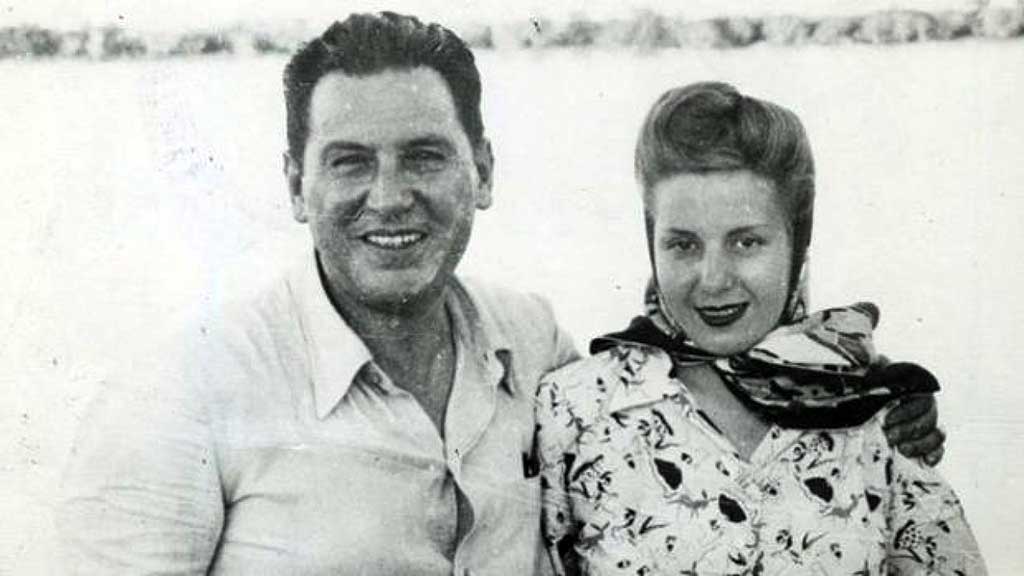

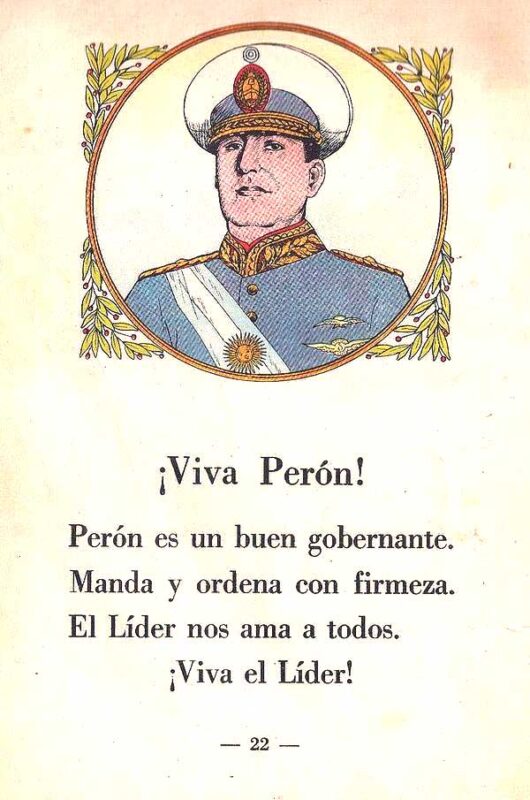

The Rise of Juan Perón

Peronism was the most glaring example of this tendency in the twentieth century.

Juan Domingo Perón ascended through the ranks of the military ruling party in the 1940’s by aligning himself with the influential trade unions.

He then won the presidency with the help of massive support from the poor and disillusioned working class.

His wife, Eva Duarte Perón, had a lot to do with his popularity.

The former actress embraced the working class and fought for the rights of women.

It was thanks to Evita that women finally got the right to vote in Argentina, in 1947.

With the help of his wife, Perón more easily painted himself as the socialist champion of the voiceless and oppressed, but he nonetheless relied heavily on military backing to sustain his rule.

He also professed a great deal of admiration for fascism and its results in Germany and Italy.

Perón’s adulation for Hitler and Mussolini explains his willingness to protect Nazi war criminals.

In the aftermath the Second World War he helped hundreds of nazis abscond to areas such as Bariloche (while — it should be noted — placing Jews in important cabinet positions).

Commodity-rich Argentina enjoyed a period of economic boom after the war, and Perón used this to his advantage.

Perón’s rule resulted in a great improvement in the quality of life for many Argentines, yet it came with the caveats of tyrannical oppression, fear and financial irresponsibility.

In his later years he would not stop at arresting and torturing dissidents, though his most common political weapon was to silence his opponents by snuffing out their forms of expression — most notably media outlets.

Like other leaders before him, as soon as chinks in Perón’s armor appeared in the form of a financial downturn resulting from isolationist policies, his enemies were prepared to attack the image of the seemingly ‘faultless leader’ and his downfall was swift.

What is unusual about Perón compared to other caudillos, is that he would rise up to lead the country, not just one time but twice.

His second term was from 1952 until 1955, when the people voted him in after turbulent years following two back-to-back military dictatorships.

His 1973 re-election for a third term revealed not only Perón’s persistence, but the population’s willingness to throw themselves at the feet of a figure postulating as an omnipotent redeemer.

Perón’s shadow still heavily looms over the contemporary Argentine political landscape.

Peronism remains the strongest political force in the country, and a series of Peronist leaders have come forward to lead the country with little foresight or temperance before being overthrown by often equally oppressive and short-sighted opponents.

The military dictatorship of 1976-81 may be viewed as a kind of multi-headed caudillo who ruled by violence and oppression.

Argentina’s murderous military dictatorship was a direct reaction to the previous authoritarian president, Perón’s unpopular widow, Isabel who served from 1974 to 1976, after Perón died.

Carlos Menem: The Peronist Neoliberal Caudillo

Carlos Menem, President of Argentina from 1989 until 1999 was in many ways a throwback to the caudillos of old.

He first established his power as governor of the La Rioja province, building up a power base there that would serve as his stronghold as he entered federal politics.

A larger-than-life character, he came to power with the newly-democratic nation suffering hyperinflation and a general sense of pessimism.

Playing the role of ‘knight in shining armor’ that has bedazzled the country’s citizens before, Menem implemented a series of economic reforms.

Menem’s reforms brought short term prosperity to the country, boosting his popularity.

The most notable among these reforms was his decision to peg the persistently troubled Argentine peso to the America dollar one-to-one.

Middle class Argentines were able to vacation in Europe and the United States, making it seem like once again Argentina was going to be able to claim its rightful place among the world’s leading nations.

Once the party ended, his drastic reforms eventually proved absolutely disastrous to the economy.

The final result was the massive financial crisis of late 2001, which left millions jobless and subsisting below the poverty line.

Néstor Kirchner, the Revitalizer After the Fall

The emergence of Néstor Kirchner, from provincial strongman in Patagonia to president of the nation in 2003, demonstrated that the modern-day caudillo still has an important place in Argentine politics.

Kirchner showed all the hallmarks: early popularity based on perceived patronage of the lower classes, promises to restore the nation’s stability, suppression of opponents through manipulation and control of the media and a seemingly endless desire to increase his personal wealth and power.

Very much a modern, softer, incarnation of the traditional caudillo, he was a blend of the political and the robust.

Maneuvers like stepping aside in 2007 to allow his wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, to run for a presidential term in order to avoid accusations of megalomania show that he was a wily operator.

This meant Cristina Kirchner was able to cement her legacy as the first woman elected president of Argentina. (Isabel Perón, Peróns widow, was Argentina’s first female president, but she was not democratically elected.)

It also made Nestór and Cristina Argentina’s most powerful political couple since Eva and Juan Perón.

It appeared the plan was to avert a two-term limit and hold onto power as long as possible by alternating terms with Cristina.

Kirchner’s darker connection to his violent forebears could be perceived through his close association with protest leaders such as Luis D’Elia from the Confederation of Argentine Workers, who operates by threatening opponents with physical violence.

It’s no coincidence that the men who were Nestór Kirchner’s closest allies on the continent, Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and, to a lesser extent, Bolivia’s Evo Morales, also fit the mold of the typical Latin American populist leader.

Nestór planned to run for again president in the 2011 election but died unexpectedly of heart failure in 2010.

His death left a large power vacuum in the perpetually volatile Argentine political landscape, as he was expected to win the election the following year.

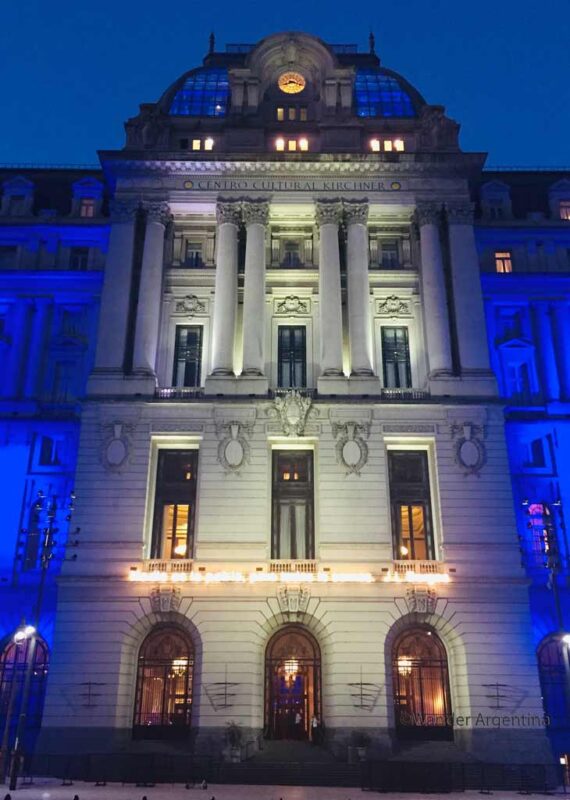

The nine-floor CCK is one of the largest five cultural centers in the world.

Cristina Kirchner, Argentina’s First Caudilla?

After Nestor’s death a was a no-brainer that Cristina would then step in and take over the presidential race in 2011, especially as the public felt great sympathy for the widow.

After her husband’s death, she wore only black for a year.

She was a martyr in mourning, who nonetheless had the strength to save the Argentine people.

She won the presidency for her second term with 54% of the vote.

Agreements were made for Russian mutual investment to develop oil fields in the Vaca Muerta and build a dam in Patagonia. It as also agreed that the Russian TV network, RT would be broadcast free on Argentine television.

—courtesy of the Casa Rosada.

CFK, as she is commonly referred to, thus served as Argentina’s president for two terms from 2007-2015.

A key to her success was doling out generous government benefits for her core constituents.

One of her key reforms was a universal child benefit plan that provides a monthly stipend for each child for families who have no employment or work in the informal sector.

Kirchner fashioned herself after Eva Perón, often being photographed next to images of Eva and erecting images honoring Eva on buildings and in public art murals.

Since the Argentine constitution only allows for a president to serve two terms, there was a movement to amend to the Argentine Constitution to allow her to serve again.

Cristina quietly supported the initiative.

In the end her supporters did not get the 2/3 vote needed in the House to change the Argentine constitution.

Twelve years of combined Kirchner-Fernández rule did not end with insurgency, popular uprising, or invasion.

Argentines voted for change with the election of neo-liberal, non-populist Mauricio Macri.

As the leader of the center-right Republican Proposal party (PRO) he was pro-business and critical of ‘Peronist Caudillos‘ operating in the provinces.

Foreign observers anticipated Macri’s election would be the end of Argentina’s love of populism.

Macri normalized Argentina’s parallel currency market, and invited foreign investment and trade.

Argentina’s first non-Peronist president in 14 years, worked to modernize Argentina’s political landscape.

His pro-business, neoliberal outlook meant he instated austerity measures.

Macri’s belt-tightening measures included firing many public sector employees (known disparagingly as ñoquis), cutting benefits and closing cultural centers, which caused him to lose support.

The Durable Influence of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in Argentine Politics

The country’s adoration of CFK is what ousted Mauricio Macri after one term.

Displaying the same, if not more, political savvy than her husband, Kirchner essential ran as Vice President against him.

In an unprecedented occurrence, it was Kirchner who effectively elected who would be ‘her president’ while she served as Vice President, not the other way around.

She chose Alberto Fernández to be her President while she would appear on the ticket as the Vice President.

The population was tepid on Alberto Fernández and political commentators maintain he won because CFK was on the ticket.

Alberto Fernández isn’t a caudillo in the typical sense — he was never a populist figure and didn’t climb to power on his own.

He has a softer, guitar playing public image, but one incident of violence toward a civilian in a bar demonstrates that he may have a hidden ruthless streak characteristic of a caudillo.

Meanwhile, Cristina Kirchner is undeniably the most influential woman in Argentine politics since Eva Perón.

A 2022 assassination attempt serves as a stark reminder of her polarizing impact on the country.

Perhaps she will go down in history as Argentina’s first caudilla.

Will Caudillismo End in Argentina?

It remains to be seen if Argentina will persist with its mercurial love-hate relationship with these arcane figures of power and passion.

For now, some might consider Juan Domingo Perón to be Argentina’s last true caudillo.

But in the time since Argentina returned to democracy, Nestór and Cristina Kirchner both exhibited leadership reminiscent of a caudillo.

For now, incumbent president Alberto Fernández has chosen not to seek reelection in 2023.

And even though she is eligible, the wildly popular incumbent vice president and former president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has also chosen not to run for a third presidential term.

Argentina’s Power Vacuum: A Breeding Ground for a New Caudillo

In 2023, Argentina commemorates its 40th year of democracy, yet the emerging power vacuum has thrust far-right libertarian candidate Javier Milei into the lead.

In a stunning upset, Milei secured the highest vote count in Argentina’s August 2023 presidential primary election.

He leads La Libertad Avanza, a far-right coalition advocating fiscally and socially conservative principles.

Additionally, he holds a seat in the Argentine congress.

Milei’s popularity reflects a response to Argentina’s high poverty rate, surging inflation, escalating crime rates, and a welfare system that has led anti-Peronists to dub the nation ‘Argenzuela.’

With a charismatic and fiery persona, Milei exhibits qualities that could classify him as a contemporary caudillo if he were to emerge victorious.

The prevailing power vacuum, coupled with the frustrations of middle-class Argentines, fuels the potential resurgence of a modern-day caudillo figure once again.

—by Dan Colasimone and Ande Wanderer

1 thought on “The Caudillo Argentino: From Rosas to Kirchner to CFK”

Comments are closed.