Boxer Carlos Monzón was the exemplar of calculated aggression in the boxing ring and, at times, a blazing, uncontrollable menace out of it.

He was Argentina’s über-celebrity of the 1970’s.

He dated the most famous movie stars, even if he happened to be married to someone else at the time.

He began as an unassuming provincial kid who went on to star in films, dress like a dandy and repeatedly beat many of his long line of glamorous girlfriends.

His early life was blighted by crime and after gaining fame and adulation as one of the world’s finest athletes, he wound up being sent to prison for murdering the love of his life.

He died at the age of 52 after crashing his car returning to prison after a day’s furlough.

In Argentina Monzón is revered as one of the greatest sportsmen the country has ever produced, alongside names like footballer Diego Maradona, Formula 1 legend Juan Manuel Fangio and of course, Lionel Messi.

Folk singer Leon Gieco’s tribute, Puño Loco (Crazy Fist) achingly remembers the boxer and his profound effect on the Argentine people despite the darker aspects of his personality.

In the boxing world he is widely regarded to be in the top three middleweights of all time.

Mike Tyson, a devoted student of boxing history while training under Cus D’Amato, has repeatedly professed his veneration for the Argentine.

“I always loved Carlos Monzón. He was a tough guy, for real, a guy from the streets,” Tyson told sports daily Olé.

“He didn’t talk much. He didn’t need to. The ring belonged to him,” he said.

Carlos Monzon: FAQ

Nationality/Birthplace:

Argentinean / San Javier, Santa Fe

Birthdate:

August 7, 1942

Height:

5’11 ft (182cm)

Nickname:

‘Escopeta‘ (Shotgun)

Major championship titles:

Middleweight (1970-77)

Total Fights:

100

Total Wins:

87

Death date:

January 8, 1995

Cause of Death:

Car accident

Monzón’s Humble Beginnings

While many boxing champions from the U.S. or Europe come from tough inner-city neighborhoods, most of Argentina’s finest fighters punch their way out of the grim frontier provinces to make their way to the bright lights of Buenos Aires in the hope of earning fame and fortune.

This is the story of Carlos Roque Monzón.

He was born in the desolate town of San Javier in the Santa Fe province on August 7, 1942.

He grew up in a humble home with his parents, who were of indigenous Mocoví ancestry, and four siblings.

The future weight champ dropped out of school in the third grade and immediately started working to support his kin.

He toiled through a range of odd jobs such as newspaper delivery boy and milkman but later he found he could also make a little money from his new hobby of boxing.

Monzón would earn up to 50 pesos by winning loosely organized backstreet bouts.

He began working his way up through the amateur ranks and came across the trainer who would shepherd him through the rest of his career and become a father figure and lifelong companion, Amilcar Brusa.

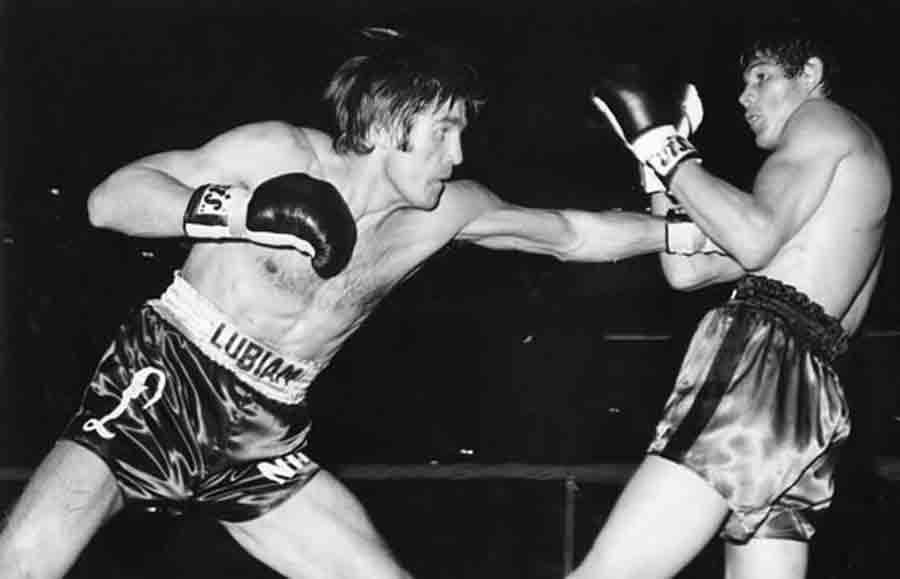

Early Boxing Career

Monzón turned pro in 1963 at the age of 20, winning his first fight with a second round knockout.

The six foot tall, hard-as-flint middleweight battled his way through 19 fights over the next two years.

He lost three times in that period in what was a merciless trial by fire for the still-developing boxer. Never would he taste defeat again in the ring.

I made the whole world talk, their hearts beat.

I made them see that everybody has blood.

—Leon Gieco, Puño Loco

Most importantly, he was taken under the wing of fight promoter Juan Carlos ‘Tito’ Lectura, patron of Buenos Aires’ boxing coliseum, Luna Park.

Revered boxing journalist Carlos Irusta first met Monzón at that time. Like many fight experts, he was not initially blown away by the Santa Fe pugilist’s aura.

“He was a very polite guy, but he didn’t talk much,” says Irusta.

“He wasn’t charismatic. At that stage Monzón was just another boxer. He didn’t give you the impression that he would go on to reach the heights that he did.”

Despite his weak first impression, Monzón’s professional reputation grew on the back of some fine victories in Lectura’s arena which were broadcast on national television.

Eventually he was given the chance to fight for the title of Argentine champion.

He surprised almost everybody by beating the highly regarded Jorge Fernandez to become champion of Argentina on 13 September, 1966.

From there, Monzón’s steady progress continued until he earned a shot at the world middleweight title against the great Italian boxer Nino Benvenuti in Rome on November 7, 1970.

Once again, nobody thought he had much of a chance of victory.

“It was a more romantic time,” remembers Irusta.

“We [the boxing community] all got together to give Monzón a farewell dinner in Luna Park. There were a lot of us, and nobody except for Brusa, Lectura and one veteran journalist, Simón Bronenberg believed in Monzón.”

The Argentine public at the time were drawn to more charismatic fighters, including Benvenuti himself, a suave boxer-cum-movie star whose face could be seen on giant billboards around Buenos Aires, recalls Irusta.

“Carlos could walk along Corrientes Street in a suit and nobody would recognize him,” he says.

“All eyes were on Benvenuti. I got the feeling that the average spectator was thinking: ‘Who is this guy Monzón, who’s going off to fight the champ?’”

The Big Fight: Benvenuti vs Monzón

The world title bout was broadcast on a Saturday afternoon in Argentina.

“Buenos Aires stopped to watch,” says Irusta.

“The next day everyone was talking about Monzón. If he’d lost, though, it would have been just another fight.”

Fight fans were in for a shock.

The brilliant Benvenuti was made to look obsolete. His punches failed to land while Monzón was precise, flawless. The final round is part of boxing folklore (watch it on Youtube here ➡).

Monzón battered and shattered the champion in the twelfth before peddling oblivion with his crazy right fist.

It was one of the purest knockouts in the sport’s history, but equally striking was the way the Argentine nonchalantly turned and strolled back to his corner after delivering the brutal blow, as if he had just punched off work at a factory rather than punched out the revered middleweight champion of the world.

Those three minutes were pure Monzón – mechanical, calculating, clever and merciless.

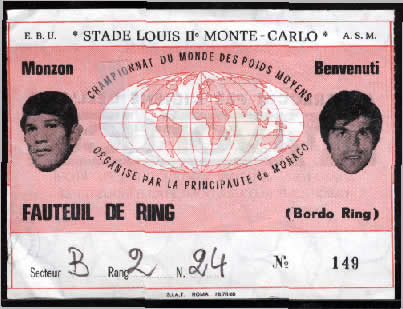

Benvenuti would get a rematch the following year in Monte Carlo but this time he only lasted three rounds.

Monzón had gone from laconic provincial hardman to international idol.

He would defend his title 14 times without loss, a feat never matched before or since in the middleweight division.

He ended his career with a professional record of 100 fights, 87 wins, 10 draws and only the three losses early in his career.

Aside from Benvenuti, he would clean up future Hall of Famers Emile Griffith and José Nápoles, as well as every other highly rated contender of his era.

Monzón ruled the middleweight division with magnificent impunity before showing the astuteness to declare his retirement on July 30, 1977 after a tough victory against Rodrigo Valdez in Monte Carlo. Upon seeing his tattered face in the mirror after the bout, Monzón knew it was time to walk away from the sport.

The Enigma of the Ordinary but Invincible Boxer

I was one more magician, hard as a rock to break,

I was the king of that dark club.

—Puño Loco

Even under the intense exposure that comes with being world champion, no opponent was ever able to solve the riddle of Monzón.

His style was neither flashy nor flawless. Numerous contemporaries would echo Carlos Irusta’s sentiments on first catching sight of Monzón in the ring — a sound boxer but nothing extraordinary.

Brusa, his trainer and fellow inductee into the Hall of Fame, recalled with amusement this typical reaction to his charger in an interview with Gente magazine.

“After he won his ninth title defense, Mantequilla [Jose Napoles]’s trainer, Angelo Dundee – who has been in the corner for Mohammed Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard, no less – said to me, ‘Brusita, how practical this guy is! He destroys you little by little,’” said Brusa.

Monzón was able to use his lanky and seemingly ungainly physique to its full advantage, confusing his opponents with an upright stance and an array of defensive twists and grapples gleaned from Brusa’s experience as a wrestler.

Add to this the granite toughness of his frame and a deceptively destructive punch from both close range and distance, and Monzón’s opponents must have felt they were scrapping with a hellacious beast scrambled out of some unfathomable Pampas backwater.

Violence, Celebrity, Prison & Death

Like so many athletes who emerged from tough, violent backgrounds, Carlos Monzón did not have the capacity to fully submit himself to the comfortable life of fame and fortune which he had earned.

In his early days as an amateur fighter he often found himself in trouble with the law. He served brief stints in prison for inciting a football riot and brawling.

Rumors, often backed up by physical evidence, of abusive behavior towards the women he was romantically involved with pursued him throughout his life.

He was shot twice by his first wife in 1973 but recovered to continue his career.

Carlos Irusta attempts to explain the anomaly of a man so controlled within the ropes of a boxing ring and yet so wild out of it:

“He drank a lot, and you could say he was a violent drunk,” says the long time El Grafico journalist and ESPN commentator.

“I believe that when he was unable to express himself with words he would respond with violence. The difference in the ring was that it was his work, and he analyzed all his aggression.

“He had an extraordinary coldness,” he said.

An explosive temper and gruff demeanor did not seem to make the boxer any less attractive to high-profile women while at the peak of his fame in the 1970’s.

Appearing in movies only made his star burn brighter, explained Brusa in the Gente interview.

“When Carlitos made the movie ‘El Macho‘, women went crazy. They threw themselves at him,” he said.

“The actress Ursula Andress came from Los Angeles to look for him,” Brusa said.

“I told him to forget about girls while he was in the ring. And he understood.”

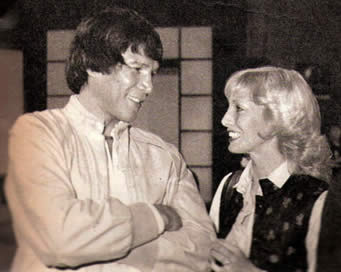

Argentina was both scandalized and enthralled when the middleweight champion began an affair with the country’s most famous actress, Susana Giménez after the two of them had starred in the movie, ‘La Mary’ together in 1974.

Monzón was still married at the time, but the relationship would continue right up until his retirement in 1977.

Giménez reportedly encouraged him to quit the sport and this, along with his increasingly decadent lifestyle caused a falling out between the boxer, Brusa and Lectura.

The diva, today one of Argentina’s most popular chat show hosts, was another of Monzón’s lovers whose face sometimes bore the bruises of his violent domestic outbursts.

It was her rumored affair with singer and actor, Cacho Castaña that was blamed for the breakup though.

A year after splitting with Giménez, Monzón met Alicia Muñíz, the woman who would become his second wife and mother to his child, Maximiliano.

Once again the relationship would turn out to be a tumultuous one, but this time it ended in tragedy.

Though officially the pair had separated, they were together in a beachside Mar del Plata condo in the early hours of the morning on February 14, 1988.

They fought, and Muñíz ended up dead, thrown from the second floor balcony.

Forensic evidence showed that the ex-boxer had also strangled her before her fall. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison for murder.

“People were stupefied when it happened. It was a Sunday during summer, when there is not much news happening. Everyone was talking about how Monzón had killed Alicia.

“There was no talk of it having been an accident,” says Irusta.

Six years later, Monzón too was dead.

Given a day’s leave of absence from prison for good behavior, he was returning by car alone in the evening of January 8, 1995 when he lost control of the vehicle.

It rolled several times and Monzón died before help could arrive. Public reaction in Argentina was mixed, says Irusta.

“On the one hand, there was a group who considered him a murderer and they crucified him,” he says.

“There were others who, on the sporting side, saw him as a great champion, and as someone who looked after his family and cared about them.

“He always maintained that he couldn’t remember what had happened that night with Alicia. When I went to his funeral in Santa Fe, people sang, ‘dale campeón’ (Go champion).”

“For the people of Santa Fe, he isn’t a murderer,” says Irusta. “Aside from those horrendous events, he is Monzón, the world champion.”

I made the heavens fall, I stopped the winds,

I made them cry with just one crazy fist.

—Puño Loco

— by Dan Colasimone

→ Read about Diego Maradona’s Rise to Soccer Stardom, his many life scandals that kept him in the news and what led up to his untimely death at 60 years old.

→ Read about the Early Start of Argentina’s Beloved Footballer, Lionel Messi

→ Read about The ‘Big Five’ and all the top football teams of Argentina