The most famous sportsman in Argentina, Diego Maradona, was never able to settle down to a quiet life of retirement after leaving football.

Drug and weight problems continued to dog him after retirement from the game.

←cont from: Maradona: The Scandals

After ballooning up to 267 pounds (121 kilograms), he underwent gastric bypass surgery in 2005.

He went to drug rehab on numerous occasions, most notably in 2000 and 2004, on both occasions discovering severe damage to his heart due to extended cocaine use.

Despite quitting drugs for a time afterward, Maradona’s was again admitted to hospital in 2007, after a binge of drinking, smoking cigars and eating to excessive levels saw his body collapse once more.

But he would get on health kicks off and on, and go on to live another 13 years.

How old was Diego Maradona when he died?

Maradona turned 60 one month before he died.

What was Maradona’s cause of death?

Maradona was recovering from brain surgery from a subdural hematoma (brain bleed) when he died of cardiac arrest.

What was Diego Maradona most known for?

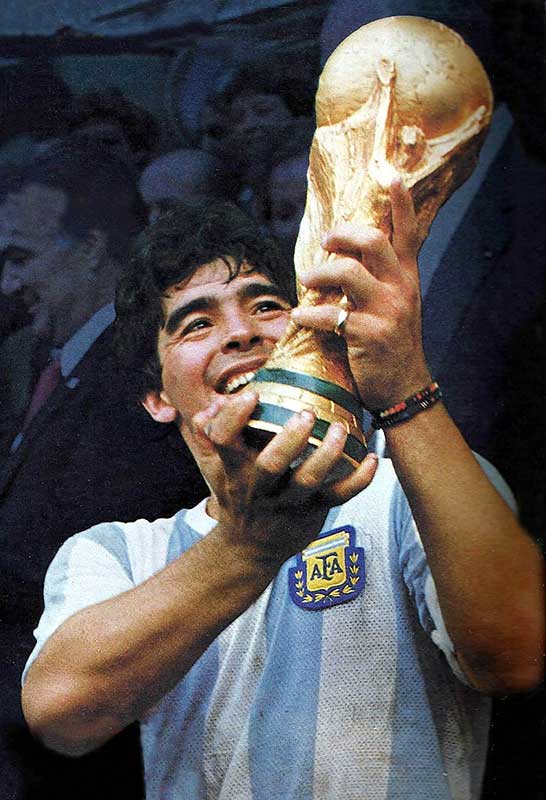

Maradona led soccer teams in Argentina, Italy and Spain to victory and won the 1986 World Cup. He also led a wild personal life with children by various women and drug use which led to later health problems.

Maradona’s Political Views

Maradona was fascinated by Latin America’s populist political leaders.

One of his first tattoos, on his arm, features Che Guevara (Lynch), the Argentine revolutionary who helped to usher in the Cuban revolution.

He later added a tattoo on his shin of Fidel Castro, whom he also publicly supported and with whom he had an enduring friendship.

Diego first met Castro on a trip to Cuba in 1987. Maradona visited in 2000 for six months of ‘detoxification’ in a rehab center, at the invitation of Castro.

Diego Maradona ended up living in Cuba for the better part of five years.

Maradona was also chummy with controversial Venezuelan leader, Hugo Chavez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro.

He declared on the Chavez’s TV program, ‘Aló Venezuela,’ “I hate everything that comes from the United States. I hate it with all my strength.”

At the 2005 Summit of the Americas in Mar del Plata, Argentina Maradona stood alongside Hugo Chavez to protest the presence of then-U.S. President George W. Bush.

When the United States elected Barack Obama in 2012, Maradona softened his anti-American stance somewhat.

He still hobnobbed with populist leaders in the Americas and even Russia’s Vladamir Putin at the Kremlin though.

Maradona’s Rivalry with Pelé

He continued a running battle over the years with the other ‘greatest player of all time,’ Brazil’s Pelé (Edson Arantes do Nascimento).

The two soccer greats traded insults regularly through the media, although the highlight (or lowlight) was probably when Pele fired a few barbs Diego’s way about his low moral standards.

Maradona responded by saying, “What do you want me to say? He lost his virginity to a man!”

The rivalry was put aside when Pelé appeared on Maradona’s popular Argentinian TV program, La Noche de 10 (The Night of Ten, after his playing number).

Diego Maradona’s chat show ran for 13 episodes on public television in Argentina in 2005.

It scored sensational ratings. Guests included Fidel Castro, Mike Tyson and Pelé.

The two soccer icons were remarkable civil, even chummy, on this occasion.

The two embraced, Maradona interviewed Pelé and they kicked the ball around a bit.

Upon Maradona’s death, the 80 yer-old Pelé wrote on Twitter,

“I have lost a great friend and the world lost a legend. There is still much to be said, but for now, may God give strength to his family members. One day, I hope, we will play football together in heaven.”

In spite of all his life controversy that followed him until the end, Maradona remained immensely popular in Argentina until his death.

Argentinian psychologist and author Gustavo Bernstein wrote in his book, Maradona: Iconografia de la Patria (Maradona, Icon of the Nation),

“No one embodies our essence more. Argentina is Maradona. Maradona is Argentina.”

*this post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase we get a small commission at no extra cost to you.

The Church of Maradona

A group called ‘The Church of Maradona’ claims to be an official religion and boasts 500,000 members from all over the Americas, Europe, Japan and even Afghanistan. For them, year zero is the year their idol was born— 1960.

They refer to Maradona with the tetragram, ‘D10S’ (a fusion of the word ‘Dios,’ or God, with his jersey number, 10).

Church of Maradona Ten Commandments:

1. The ball does not stain (one’s reputation), as D10S said in his tribute.

2. Love football above all things.

3. Declare your unconditional love for Diego and good football.

4. Defend the Argentina (soccer) jersey, respecting the people.

5. Spread the miracles of Diego throughout the universe.

6. Honor the temples (stadiums) where he preached (played) and their sacred robes.

7. Do not proclaim Diego to be unique to one single soccer club.

8. Preach the principles of the Maradonian church.

9. Take on Diego as a middle name and name your son Diego

10. Don’t be the ‘head of a thermos’ and don’t ‘let the turtle escape’ (this one is heavy lunfardo but it means ‘don’t live detached from reality and don’t be useless’).

⇒ Sign up for a free 30-day trial of Amazon Prime to watch, ‘Hero: The official film of FIFA World Cup Mexico 1986‘ or buy the DVD ‘Maradona by Kusturica‘ which debuted at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival.

Maradona’s Managerial Career

It was this fervent, religious-level of popularity that earned Diego Maradona, an almost completely inexperienced trainer, the unlikely opportunity to coach his beloved Argentina national team at the World Cup in 2010.

With the team struggling in qualifiers, and previous coach Alfio Basile deciding to quit his post, Argentinian Football Federation members decided to pander to popular will and name Maradona as the next coach.

The decision was met with disbelief throughout the footballing world, and even among a lot of Argentina fans.

They were prepared to love him as a player, but could someone whose behavior could be described as — at best — erratic actually lead the powerful national team to success?

In the end, despite the talent of the Argentina team, the answer was a resounding ‘no’.

Maradona had overseen a typically unpredictable qualifying campaign, which saw the team suffer heavy defeats to the mighty Brazil, and the minnows, Bolivia.

Eventually in the preliminary rounds the crucial games were won, though, Diego once again courted controversy by telling critical journalists that they could, “Suck it, and keep sucking it!”

Before naming his surprising final squad to take to the tournament in South Africa, Diego managed to run over a cameraman’s leg in his car.

Rather than stopping to apologize, he drove off shouting, “What an asshole you are! How could you put your leg under the wheel, man?”

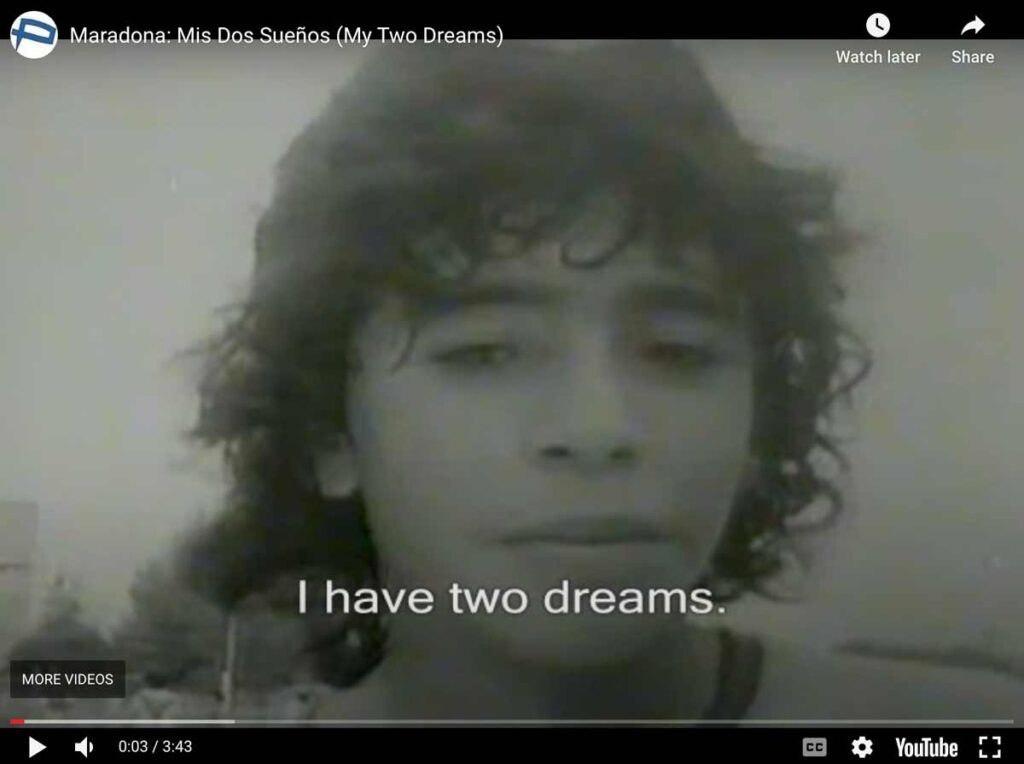

In a grainy interview in 1975 with a pubescent Maradona, he comes across as shy but determined.

“I have two dreams,” he says with self-assurance that contains none of his later braggadocio.

“My first dream is to play in the World Cup. And the second dream is to win it.”

Even that shaggy-haired teenager, already confident in his own talent, probably didn’t dare to imagine that one day he would be entrusted to lead Argentina to the World Cup, not as a player, but as the guy in the suit: the coach.

The 2010 World Cup tournament in South Africa proved that greatness on the field does not necessarily translate to greatness off it.

It was Argentina’s new soccer messiah, then 22-year-old Lionel Messi‘s first World Cup as a starter for Argentina’s national team.

Maradona, who constantly claimed that God was on his side during Argentina’s campaign, was demoralized to the point of tears after his team’s 0-4 loss to Germany in the quarter final.

To fans it seemed inconceivable that the team could lose with the natural heir to Maradona’s throne on the team.

Messi was heavily guarded by the Germans though and while he made many assists, he scored no goals in the tournament.

Life in Argentina came to a halt during the deciding game against Germany.

Even though they lost, in typical Argentine style, people took to the streets to celebrate anyway, just as they did when Maradona died.

(Link opens in a new window)

Even Maradona himself doubted his own coaching ability telling Olé, “It was much easier being a player: I only thought about getting the ball and enjoying myself.”

After calls by many for Maradona to step down as coach, the Argentinian Football Federation chief, Julio Grondona refused to fire him, saying,

“The decision depends on Maradona. The only person in Argentina who can do whatever he wants is Diego.”

After that disastrous 2010 World Cup, Maradona did leave the management of the National team a few weeks later and went on to manage a string of second rate teams.

The first team he managed overseas was Dubai club, Al Wasl FC in 2011 in the United Emirates.

That didn’t last long. He was sacked a year later with a year left on his contract after the club finished eighth in the 12-team league and failed to win any domestic trophies.

In 2013 he became an assistant coach at at Argentina’s Deportivo Riestra an Argentine Division B team, where he stayed for four years.

In 2017, Maradona became the technical director of Fujairah, a second division team in the United Arab Emirates. He was again fired before the end of the season after the team failed to ascend to the first division.

Maradona joined the Mexican second division team Dorados de Sinaloa in 2018, again as technical director.

In Mexico Maradona helped raise the profile of the team and had a close relationship with players.

He never moved into the house the team provided for him though, preferring to stay in a hotel.

He was also heavily medicated with narcotics for his various injuries during this time period though.

When the team didn’t make the first division, Maradona flew back to Argentina for various surgeries. He never returned to Sinaloa, blaming his poor health.

In 2019 Maradona returned as the head coach of Gimnasia de la Plata, a team based in La Plata, Buenos Aires’ provincial capital.

Even though the Gimansia did not perform well under his leadership, in June 2020, they renewed his contract.

Maradona’s Final Public Appearance

Gimnasia’s first game of the season took place on Maradona’s 60th birthday, October 30, 2020.

Fans in the stadium and across the country watching on TV were shocked when they saw Maradona come onto the field before the game.

Maradona had to be helped onto the field, with two assistants on either side, aiding him to walk at a slow place.

After he was presented with a cake and fireworks to celebrate his birthday, he was interviewed on camera.

His voice was so weak in the interview, that they had to remove his face mask so that he could be heard.

The appearance did not bode well.

Just a couple of days later Maradona was admitted to the hospital for what doctors said were mental health reasons.

It had largely been reported in Argentine media that the normally social Maradona was not doing well psychologically during quarantine.

He away from his family, taking antidepressants and puttering around a relatively humble home in the Buenos Aires’ suburb of Tigre that had been rented for him by handlers.

Maradona underwent emergency surgery to remove a blood clot a day later, on November 3, 2020.

The surgery was deemed successful and he was released from the hospital a week later, with orders to have close medical supervision at home.

Maradona’s longtime doctor, Dr. Alfredo Cahe criticized the decision to release him so early, saying on Telefe Noticias,

“They didn’t take care of him as they should have. He should have kept in hospital, not in a house which wasn’t properly prepared. I’m in a state of complete shock.

“After so many ups and downs with Diego for 33 years and he just died in an unusual way.”

God is Dead: Maradona Dies Unexpectedly

On November 25, 2020 reports of the Argentine soccer icon’s death came in on live TV.

The ‘Cosmic Kite’s’ sudden death of cardiac arrest at 60 years old shocked the nation.

Just a little over two weeks after his successful surgery, Diego Maradona died suddenly at his home in the leafy Buenos Aires suburb of Tigre.

Six ambulances were rushed to the scene and healthcare workers tried diligently to resuscitate him, but it was futile.

On Argentina’s ESPN sports show midday program reporters were so shocked they hardly knew what to say as they held back tears live on the air.

Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández posted a picture of him hugging Maradona on his 60th birthday on Instagram and Twitter writing,

You took us to great heights. You made us enormously happy. You were the greatest of all. Thank you for existing, Diego. We are going to miss you the rest of our lives.

– Argentine President Alberto Fernández

National flags across Argentina were put to half staff. Three days of national mourning were declared.

Fernández, a lifelong fan of Argentinos Juniors (the first team Maradona played for) gave Maradona’s family the option of holding his wake in Argentinos Jrs. stadium, or the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s Government House.

Maradona’s ex-wife Claudia Villafane chose the Casa Rosada.

Maradona’s coffin was draped with the Argentine flag with three of his number 10 jerseys: Argentinos Juniors, Boca Juniors and the Argentine National Team.

Tens of thousands of Argentine citizens came to the Plaza de Mayo in front of the Presidential Palace to pay their respects as the body of Maradona lay in state in the Government House’s rotunda.

It was anticipated that a million fans would come to visit the coffin and say their goodbyes.

Those who were not fans of Maradona (and there are quite a few of his countrymen who feel he was a poor representation of Argentina for the world) complained that the mass event was being allowed during a pandemic when children weren’t even allowed to attend school.

Before all the Maradona mourners were able to make their way to the coffin, fans took over the inner courtyard of the Casa Rosada.

They closed the front gates so that more fans couldn’t enter the rotonda.

There were skirmishes with police, who used tear gas.

On November 26, Maradona’s family decided to cut Diego Maradona’s public wake short due to the violence.

They held a private service the same day.

Maradona was buried next to his parents at the Jardín de Bella Vista cemetery in the province of Buenos Aires.

Criminal Charges in Maradona’s Death

Argentina’s justice department soon began examining if there was negligence in Maradona’s medical care toward the end of his life.

Upon his hospital release, his psychiatrist had requested his home-care include: full-time nurses (preferably male, he added) with specialization in substance abuse, a neurologist, a full-time doctor and an ambulance with a defibrillator on stand-by.

Out of all the requests, he only had a nurse present 24 hours a day, but it was Maradona himself who didn’t follow doctors orders or want to be controlled by a strict protocol claims his doctor.

Indeed, in one of the final pictures of Maradona taken he is resting on a couch with a glass of wine next to an ashtray full of cigars.

Nevertheless his neurosurgeon, Leopoldo Luque’s house and private clinic were raided by police to see if he was negligent in his care of Maradona.

Luque said in a press conference soon after his death, that Maradona was a difficult patient who wanted to be alone toward the end of his life.

He added that his role in Maradona’s care ended after the brain surgery, weeks before.

Luque was charged with manslaughter, along with six others, including psychiatrist Agustina Cosachov.

The charges came after a medical board determined that Maradona’s care was ‘inadequate, deficient and reckless’ and he died unnecessarily.

The criminal inquiry into Maradona’s death is ongoing.

Maradona’s Net Worth and Assets

Maradona earned about $500 million during the course of his career, but he was a big spender.

At the time of his death his net worth was about $75-100 million according to Argentine journalist, Julio Chiappetta.

Shockingly, but in keeping with his chaotic lifestyle, Maradona left no will or documentation clarifying how his assets should be divided.

Not surprisingly, there are a number of warring factions clamoring for a piece of Maradona’s assets.

Even the Italian government claims a large chunk of that fortune. Italian officials say Maradona dodged a $42 million tax bill white playing in Napoli.

Maradona vowed never to pay it.

In Argentina, upon death, most of one’s assets are passed to the spouse and children.

Maradona was unmarried at the time of his death, but still has a number of children (the exact number of which is not known). All of his children are entitled to a portion of his wealth.

For many years Maradona denied having any other children other than his daughters, Dalma and Giannina, from his first marriage to Claudia Villafañe.

In later years, Maradona acknowledged that he had five children from four different women.

He is also believed himself to have fathered perhaps another several children in Cuba during his years spent in the country.

Some claim he has possibly more in Argentina as well, although two possible heirs who have come forward were found not to share the Maradona family’s DNA.

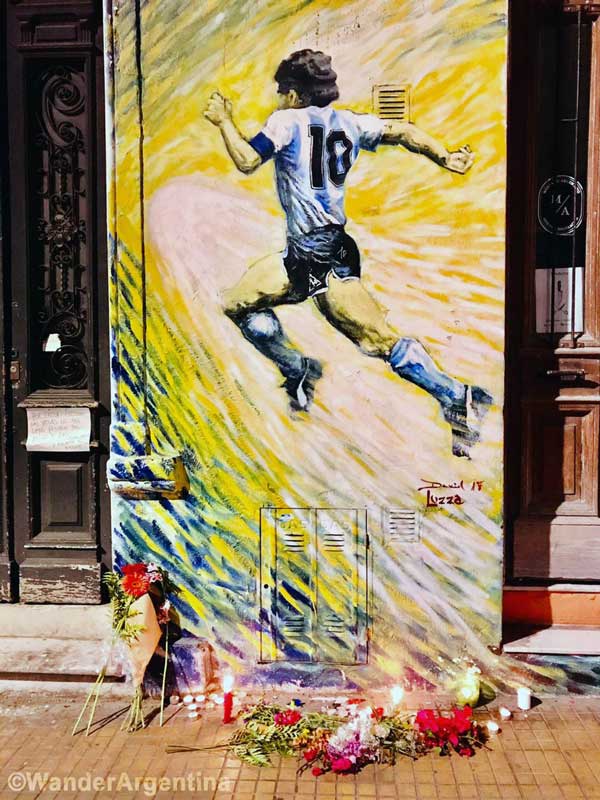

Maradona’s Legacy

In Argentina, the legacy of the soccer career and wild life of Diego Maradona will live on at the level of other icons of the country who met tragic deaths, such as Eva Perón and Che Guevara.

After all, to some he is a ‘God.’

For Argentine and football fans world over, Diego Maradona represents the triumph of an underdog.

He rose from poverty to become one of the best’s players in history starting his professional career ten days before his 16th birthday, making him the youngest player to ever compete in Argentina First Division Football.

He helped make underdog teams champions.

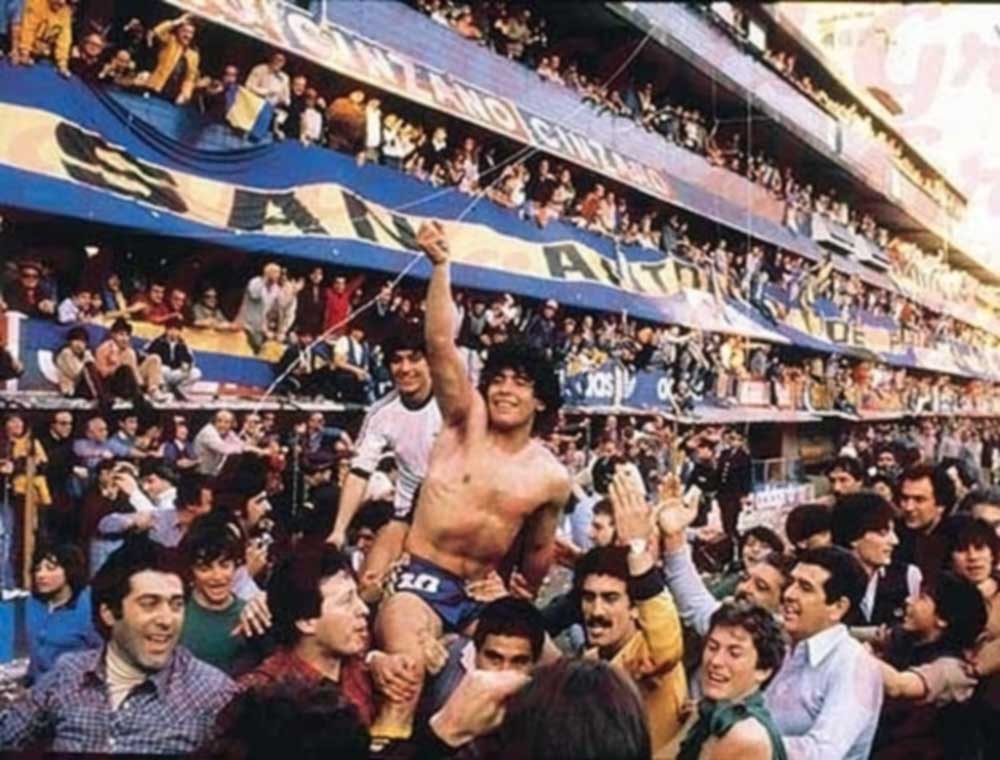

With Boca Jrs. in 1981 he took the team to win the league title, his only domestic title win.

In Napoli he is revered because he helped the team secure the only two league titles they had ever won.

He cemented his legacy with the controversial 1984 World Cup win playing for the Argentine national team.

His chaotic managerial style didn’t stop him from being made head coach of the Argentine National Team at the World Cup in 2010.

He continued to coach until his death, leading second divisions teams in Argentina, the UAE league and the Mexican league before his death.

In 2021 Amazon Prime released a celebrated series on the life of Maradona called Sueño Bendito (Blessed Dream).

If you don’t have Amazon Prime, you can sign up for a thirty day free trial to watch the program.

Maradona on His Own Death & Legacy

Maradona said on his 2005 TV program that ‘getting old with my grandchildren by my side would mean I could die peacefully.”

That was a wish that obviously went unfulfilled — even his youngest son, Diego Fernando (the second of his children named Diego) was only seven at the time of his death.

Maradona added that he was most grateful for having played football.

“It’s like I touched the sky with my hand,” he said at the time.

When asked what words he would want on his tombstone, he said, “Thanks to the ball.”

Maradona left behind eight recognized children, three grandchildren and an entire nation of lifelong fans.

—by Dan Colasimone & Ande Wanderer

⇐ Diego Maradona: The Man, the Myth