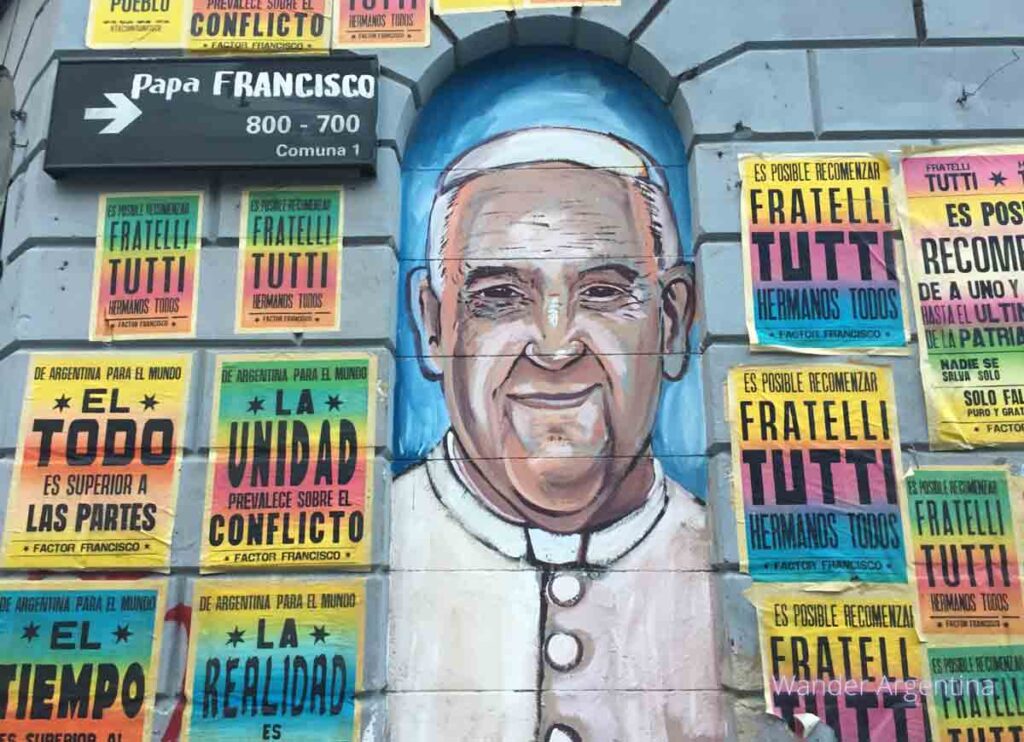

Pope Francis is most revered among the people of the slums of Buenos Aires.

Back then, when he was still in Buenos Aires they knew him simply as Bergoglio, or Father Jorge.

He spent much of his time in places such as villas 21-24, shantytowns where he would wash the feet of the poor, give confessions and hold communion.

“He was close to this community, and always present. People appreciated it very much,” says Father Sebastian Risso, a parish priest in villa 20.

A church in which priests would actively engage marginalized communities was part of Bergoglio’s missionary vision.

After being appointed Bishop of Rome in 2013 his objectives remained the same.

The world was intrigued as he spent his first Holy Thursday washing the feet of prisoners instead of priests.

For those who knew him as Father Jorge, Argentina’s Cardinal, it came as little surprise.

“He hasn’t changed,” says Risso. “He does the same things he did in Buenos Aires.”

Pope Francis’ Early Life

Jorge Mario Bergoglio was born in 1936 in the working class barrio of Flores, Buenos Aires. Though by birth a Porteño, or native of Buenos Aires, Bergoglio’s father was from Piedmont in Northern Italy, having moved to Argentina with his parents to build a life away from Benito Mussolini’s regime.

Bergoglio developed a special connection with the Catholic faith thanks to his grandmother, Doña Rosa Margherita Vasallo de Bergoglio.

“It was my grandmother who taught me to pray,” he said in a 2012 radio interview with Father Juan Isasmendi on community radio of villa 21, Buenos Aires. “She taught me a lot about faith and told me stories about the saints.”

Nonna Rosa was not an ordinary Catholic; she inspired Bergoglio with her particular brand of religious activism.

In Italy she had been a member of Catholic Action, an anti-fascist movement created by Italian bishops to speak out against Mussolini’s regime in the 1920s.

Thanks to her influence, but against the wishes of his mother, Bergoglio joined the Immaculate Conception Seminary at the age of 19 to study theology.

Throughout his studies Bergoglio held a long list of alternative job titles and interests outside of the faith.

He worked as a janitor, lab technician and, at one point, a bar bouncer.

Like many other Argentines in their late teens he enjoyed dancing tango with his friends and watching his favorite soccer team, San Lorenzo, play matches.

In 1958, at the age of 21, Bergoglio entered the Society of Jesus as a novice and two years later he officially joined the order, taking the vow of poverty, chastity and obedience.

This post may contain affiliate links. We may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

The Jesuits, the Pope and the Dirty War

Bergoglio spent his first few years with the Society of Jesus teaching and studying at universities. He rose quickly within the hierarchy and became Provincial Superior of Argentina by the time he was 36 years old.

Later on, Bergoglio attributed missteps and an over-authoritarian style during this controversial time of his career to his age and inexperience.

Bergoglio faced both internal and external challenges when he came to the order, first while Juan Domingo Péron was president and then after the 1976 coup d’état

. Throughout the years of the bloody war in Argentina, the military dictatorship began disappearing those they believed to be sympathizers of left wing political ideology.

The Jesuits came under threat because of the particular brand of liberation theology they followed.

This Latin American movement, which began in the 1950s, encouraged priests focus their work on supporting the poor in fighting political and economic oppression.

At the time, Pope John Paul believed the Jesuits were attaching the gospel too closely to social causes. He feared the slum priests were conspiring with guerrilla movements, so he sent orders to disband their work.

Bergoglio has been criticized in particular for failing to protect two Jesuit priests, Orland Yorio and Francisco Jalics, after they were arrested and tortured.

The pair had disobeyed Bergoglio’s orders to live outside of the slums, although he allowed them to continue working there.

Argentine investigative journalist Horacio Verbitsky released a report suggesting Bergoglio colluded with the dictatorship.

An Argentine human rights lawyer filed a criminal complaint in 2005 that contained few details and went nowhere, even after Bergoglio testified.

Pagina 12, the newspaper that published Verbitsky’s accusations, has since removed the articles.

Bergoglio denied the charges but admitted that the church could have done more to protect those killed.

He had bishops issue a collective apology in 2012 for the church’s failures to protect people during Argentina’s dictatorship. The apology blamed both the government and leftist guerrillas for the violence.

‘Bergoglio’s List: How a Young Francis Defied a Dictatorship and Saved Dozens of Lives’ claims that Bergoglio actually worked in secret throughout those years to protect priests and help those captured.

Argentine Jesuit Father Juan Manuel Scannone said in the book, “It took us years to realize the complete truth about Father Jorge’s rescue efforts.”

Since his appointment, Pope Francis has ordered the Vatican to open its files for an investigation into the Dirty War era, with the goal of discovering the fate of at least some of the estimated 30,000 victims.

Cardinal Bergoglio and Buenos Aires

Bergoglio’s early leadership and resistance to the Marxist tones of liberation theology fostered an ideological divide among the Jesuits in Argentina.

But after a humbling personal transformation during a five-year church-imposed exile in Germany and later Cordoba, Argentina he returned to Buenos Aires, where he earned the adoration and support of much of the local clergy, especially young clergy.

As bishop, and later archbishop, he gained a reputation as approachable and down to earth, never too busy to advise the younger priests.

“One feature that stands out in terms of dealing with priests is that he was always willing to assist us immediately,” says Risso, who first met Bergoglio after entering the seminary in 1998. Bergoglio is famed for having a phone installed in his home so that priests could call him at any time of day.

‘A church that stays in the sacristy too long gets sick’ was one of Bergoglio’s catch phrases.

For the future pontiff the most important thing was breaking down the walls of the church, dismantling any perception of a hierarchy and being accessible. This coupled with the Jesuit vow of poverty, meant that he lived life as humbly as possible and among the people.

As archbishop he traveled to work on Buenos Aires’ subte and lived in an austere room.

When he was appointed cardinal in 2001, he had his predecessor’s robes tailored rather than buying new ones and refused to have meals prepared for him.

People in the most impoverished communities of Buenos Aires, a city where class divides run deep, noticed. In ‘Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio,’ a bricklayer from the parish of Our Lady of Caacupe in the Barracas neighborhood demonstrates the relationship he had with parishioners.

“I am proud of you,” said the man to Bergogolio, “because when I came here with my companions on the bus I saw you sitting in one of the last seats like one of us. I told them it was you, but no one believed me.”

Not everyone in Argentina was a fan of Bergoglio however.

It was well-known that Bergoglio had a hostile relationship with ex-president and current vice president, Cristina Kirchner. Their most public clash was over Argentina’s legalization of gay marriage in 2010.

Bergoglio called it a “a plan to destroy God’s plan.”

Kirchner was perturbed enough to address the issue while on a high-stakes trip to Beijing, describing Bergoglio’s comments as, “reminiscent of the times of the Inquisition.”

Their conflict was more deeply rooted than this single issue however and stretches across both Kirchner administrations.

Following the economic crash of 2001, Bergoglio openly denounced the increasing levels of poverty in Argentina.

He frequently spoke out against ‘unrestrained capitalism’ and the ‘neo-liberalism’ that had led to the crisis.

The government saw his comments as a thinly veiled attack. Néstor Kirchner described him as the ‘spiritual head of the political opposition.’

Eventually relations became so strained that both Kirchner administrations stopped the customary attendance to his annual ‘Te Deum’ prayer service to avoid listening to his criticisms.

Cristina Kirchner never attended one sermon while in office nor invited Bergoglio to meet with her in the Casa Rosada, (Argentina’s Government House) even though it’s just a one minute walk across the Plaza de Mayo from the Cathedral.

After he was appointed Pope, the relationship between the two outwardly improved as Bergoglio’s newly found global influence meant his popularity soared and Cristina took every opportunity to associate with him.

Argentina’s next president, Mauricio Macri also displeased Bergoglio over gay rights while he served as mayor of Buenos Aires.

While it’s been widely circulated that early in Macri’s career he called homosexuality a ‘sickness’ in an early television interview, as mayor Macri did not challenge a ruling in favor of a gay couple’s right to marry at city hall.

Allowing the ruling to stand paved the way for legal gay marriage in Argentina. Macri, a practicing Catholic, is loyal follower and attended Francis’ inauguration in Rome while still serving as mayor.

As a Peronist sympathizer, Francis had a deeper relationship with Macri’s opponent, former Buenos Aires governor and vice president under Néstor Kirchner, Daniel Scioli.

In an audience at the Vatican a few days before elections Francis asked Argentines ‘to vote with their conscious,’ which Scioli himself touted as endorsement of his campaign.

After Macri won the 2015 presidential race by a small margin, the media questioned why the pope did not call to congratulate him.

Francis said it wasn’t normal protocol to do so, although he also surely recalls Macri’s days as a ‘tabloid playboy’ on the elite Argentine social scene and clearly dislikes the free-market ideology that made Macri a millionaire.

Further complicating their relationship were accusations that swirl around the First Lady, Juliana Awada, daughter of Syrian immigrants turned successful businesswoman.

Awada has dodged complaints for years that her textile company uses sweatshop labor in clandestine factories — in the very same Buenos Aires’ neighborhoods where Francis worked with his most faithful.

Pope Francis: A New Direction for the Catholic Church?

“Francis, rebuild my church.”

According to the Bible, these were the words of Christ on the cross to St Francis of Assisi and likely what the cardinals had in mind when they were electing a new leader.

At the time they were submitting their votes in March 2013, the Catholic Church was facing a crisis.

The last two years of Pope Benedict XVI’s administration had been full of scandal.

Ongoing revelations of sex abuse within the church as well as personal documents leaked to the media pointed to both financial corruption and a power struggle within the Vatican.

#1 — First Latin American Pope

The choice of Bergolio to lead the church seemed to be a strategic departure from the status quo.

Over 1,200 years had passed since someone outside of Europe had been elected and it was the first time a Latin American had been chosen.

Some of the first measures that Pope Francis took as leader involved restructuring the financial handling of the Vatican. This is part of his vision of a ‘poor church, that is for the poor,’ as he announced to the media the day after he was elected.

He told the press the same day that the name ‘Francis’ had actually come to him in the voting enclave itself after a cardinal had turned to him and said, “Don’t, forget the poor.”

Tackling poverty was at the top of Bergoglio’s agenda in Buenos Aires and that didn’t change when he became pope.

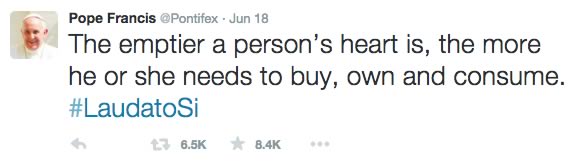

In a Papal Exhortation he calls on world leaders to ‘guarantee dignified work, education and health care for everyone.’ In the same communication he describes economic inequality in the world as so severe that it could violate the sixth commandment ‘thou shall not kill.’

Pope Francis is not the first pope to call for an end to global poverty. But why does his delivery of the message in speeches and writings make headlines around the world?

“It is his experience, and his pastoral sensitivity and his sentiment of Latin America that makes the difference,” says Risso.

As pope, Francis still repudiates the use of limousines and the papal residence in the Apostolic Palace, instead living in a simple two-bedroom Vatican apartment.

His handlers worry that he doesn’t wear a bulletproof vest and sometimes sneaks out at night to wander the streets and minister, just as he did in Buenos Aires.

Francis’ appointment repaves a social and cultural space for the Catholic Church in Latin America. Part of the reason for this is the friendly relationship he holds with Evangelicals.

South America is home to more than 40% of the world’s Catholics, but their numbers in the region have been waning for many years as more people move to the Evangelical faith.

While still in Buenos Aires, Bergoglio had strong ties with Pentecostal priests. As pontiff, he has described the divisions between different factions of the church as ‘the work of the devil.’

The church still remains an important part of the Latin American political landscape, probably more than any other continent. Describing, ‘trickle down economics’ as ‘naive’ and ‘the cult of money’ as ‘the worship of the golden calf,’ is music to the ears of left wing governments in Latin America.

Among his supporters in Latin America was Fidel Castro, who told the pope he was considering joining the Catholic Church during a visit during an informal encounter in Havana, a year before Castro’s death.

The pope’s leverage allowed him to play an important role in the return to normalized relations between Cuba and the United States and shows the Catholic Church taking a healing role in international politics.

If his anti-consumerist, pro-conservation views are received well in much of South America and other developing regions, they present a challenge to the conscience of the wealthy Catholic contingent in the United States.

A 2015 Gallup Poll found that the pope’s approval rating among U.S. Catholics fell from 89% to 71% between 2014 and 2015.

Among U.S. conservatives it fell from 72% to 45%.

The media deemed it conspicuous that Roman Catholic justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and the late Antonin Scalia were no-shows at the pope’s historical 2015 address to a joint session of Congress.

“Pope Francis speaks extemporaneously with more frequency than his recent predecessors. Seemingly innocuous statements are isolated by media, then repeated throughout 24-hour news cycles in relative contextual isolation,” says Wayne Laugesen, contributer to the National Catholic Register and editorial page editor of the Colorado Springs Gazette (USA).

“The distortions of casual statements, willful and otherwise, have led to a feeling of disenfranchisement among traditional American Catholics.”

While on his first U.S. visit as Pope, the media frenzy caused the Vatican press office to go into damage control mode.

When Francis met with Kim Davis, the state of Kentucky County Clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to gay couples, it made international headlines.

It was less widely-publicized that the pope met with Yayo Grassi, an openly gay former student of his, the previous day.

Grassi and his family, including his partner, had a private audience, after the pope personally called his ex-alum to arrange the meeting weeks before. Grassi told the media that Francis has known he is gay for decades, and was never judgmental about it.

Despite his struggles with politicians over gay marriage in Argentina and loyalty to church doctrine on the matter, his wider message as pope is one of inclusiveness.

He famously asked reporters on a flight back from World Youth Day in Brazil, “If a person is gay and seeks God and has good will, who am I to judge?”

The pope’s address to the U.S. Congress was well-received by politicians on both sides of the aisle, and his artful comments on key issues supported the positions of both U.S. political parties.

After only uttering a few sentences, the pope received a standing ovation and had some attendees, including former Speaker of the House John Boehner and Senator Mark Rubio, openly weeping.

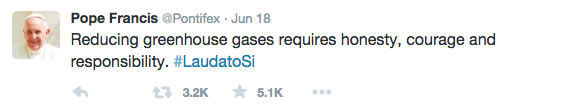

In the address, Francis highlighted the need to focus on protection of the environment arguing that, “We need a conversation which includes everyone, since the environmental challenge we are undergoing, and its human roots, concern and affect us all.” He was quoting directly from his encyclical letter, ‘Laudato, Si.’

Laudato Si, with its focus on ‘integral ecology’ was so controversial that part of it was leaked to the media before its release by internal Vatican sources unhappy with the contents.

It was the first encyclical to be dedicated completely to environmentalism.

Hardliners within the church believe that a pope should only discuss spiritual matters.

Pope Francis’ focus on the environment is keeping in tune with his namesake ‘St Francis of Assisi,’ the patron saint of ecology.

He showed the world “just how inseparable the bond is between concern for nature, justice for the poor, commitment to society, and interior peace” wrote Francis in Laudato Si.

If American Catholics and wealthy politicians are made uncomfortable by Francis’ focus on the environment and discourse that sounds far too socialist for those operating in the cradle of ‘unjust economic structures’, his message has been embraced by leftist figures in the U.S.

Former U.S. Democratic presidential contender, and current senator, Bernie Sanders released a statement after the pope’s congressional address that read,

“Pope Francis is clearly one of the most important religious and moral leaders not only in the world today but in modern history. He forces us to address some of the major issues facing humanity: war, income and wealth inequality, poverty, unemployment, greed, the death penalty and other issues that too many prefer to ignore.”

The pope further highlighted his message on his U.S. trip by shunning the formal state lunch with his congressional hosts after his speech, to instead dine with the homeless and give blessings at a Washington D.C. soup kitchen.

“Pope Francis makes the world a better place by advocating for the poor and reminding us of the importance of charity. But Catholic charity relies entirely on pursuits of profits the pope characterizes as a cause of poverty,” says Laugesen about Francis’ anti-capitalist comments to policy makers.

“Pope Francis is a brilliant, kind and loving man who, as Christ’s vicar on earth, cares about every man, woman and child. Alas, he is not an economist.”

Risso says there is no difference in the teaching of the Bergoglio he knew and the pope of today, only a change of audience.

“He just preached the gospel – just a simple preacher, but it’s the Pope speaking to the U.N. and the U.S.”

And, in a difficult time, to the world.

“His way of being present – I think that changes the church,” says Risso.

“He is with the people, as simple as that, like Jesus, there with the people, with the suffering ones.”

-Maral Shafafy & Ande Wanderer