The Plaza de Mayo is as fundamental to Argentine political history as La Boca and homesick immigrants are to tango.

The square is a political hub, financial and administrative center and throughout history has been a symbol of disaster, rebellion and hope.

In May 1810 the revolution began in what was then called the Plaza de la Victoria.

Six years later Argentina won independence from Spain and the square was given its current name, May Square.

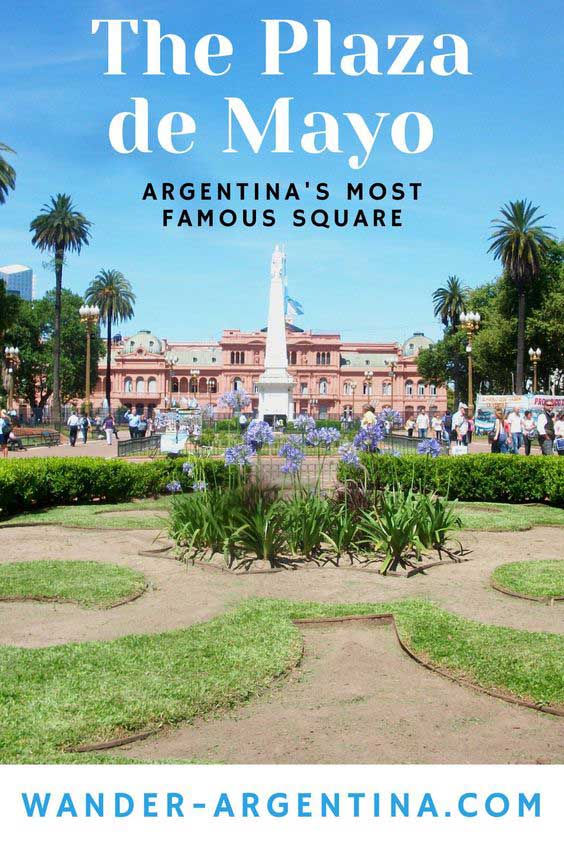

Among the three important historic buildings on the plaza, are the Cabildo, the former seat of the Colonial government, the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Cathedral — now famous as Pope Francis’ former parish, and of course the government house, the Casa Rosada.

Communities from all walks of life convene to voice their political opinions in the square.

In the Plaza de Mayo visitors may see workers going about their business, political marches, protests, gawping tourists taking snaps, TV camera crews, and eccentric old folks feeding large flocks of pigeons and veterans of the Malvinas/Falklands conflict, who have set up up protest camps here off and on,

⇒ To learn all the history of Plaza de Mayo with a knowledgeable local, sign up for a two-hour walking tour tour of Plaza de Mayo

Peronism in the Plaza: Juan Perón and Evita

One of the most dramatic events to change Argentine history occurred here on October 17th, 1945, today celebrated as ‘Loyalty Day.’

Thousands gathered in the square to demand the release of Juan Domingo Perón, who held an important government position at the time but had been imprisoned by his own party – they viewed his growing popularity as a threat.

This sealed Perón’s fate as a working class hero.

He was released by the government after this protest and became president a year later.

Following his election it became tradition for families to gather in the square on national holidays, particularly on May 1st, (Workers’ Day), and on May 25 (May Revolution Day).

President Perón and his wife Maria Eva Duarte, affectionately known as Evita, famously delivered their speeches from the balcony of the Casa Rosada, to the thousands of supporters, known as descamisados (shirtless ones), gathered in the square.

Bombings in the Plaza de Mayo

A tragic event in the square’s history occurred on April 15th, 1953 when two members of the opposition party, Roque Carranza, planted two bombs during a political gathering.

Five people died and 95 were injured.

(Strangely, there is a Subte station named after Carranza, who later became the Defense Minister, on the upscale D line that goes to Palermo and Belgrano)

Two years later, on June 16th the square was bombed once again by the Argentine Air Force in an attempt to overthrow Perón’s government in what is remembered as La Masacre de la Plaza de Mayo (May Square Massacre).

Thirty-two planes shot over 9.5 tons of shells on the square and although the death count has been subject to debate, it is now thought to be 321, and more than 700 injured.

Today visitors can still see bullet holes on some of the buildings surrounding the plaza.

The coup attempt was an abject failure, but three months later, the armed forces joined together and overthrew Perón’s government in another attack.

The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo

One of most emblematic symbols of the Plaza de Mayo are the Madres de la Plaza or Mothers of May Square.

These are women whose children were ‘disappeared’ by the military dictatorship (1976-1983).

The mothers demanded to know where their children were and began to march around the May Pyramid in the middle of the square wearing handkerchiefs with their children’s’ names embroidered on them.

The weekly marches started in 1977 and continue today – you can see the mothers and their supporters every Thursday afternoon in the plaza.

While in the plaza you can take a free tour of the Casa Rosada and visit the Bicentenary Museum around the corner.

Also check out the affordable Buenos Aires walking tour, which covers downtown, the Plaza de Mayo and very usefully gives visitors a primer on using Buenos Aires’ Metro and Bus systems.

Protests & Cacerolazo’s in the Plaza

More fresh in the mind of Argentines, are images of the plaza during the 2001 economic crisis, or corralito, where thousands of people banged pots and pans (in what’s known as a cacerolazo) in the Plaza de Mayo to protest withdrawal clamps and devaluation of their savings after the government converted them into the much weaker Argentine currency.

There were violent incidents between the police and protesters across the country and the police killed five people in the Plaza de Mayo.

Just as Isabel, Perón’s second wife had done in 1976, the sitting President, Fernando De la Rúa famously ‘escaped’ from the Casa Rosada by helicopter after resigning.

Tens of thousands still sometimes fill the plaza and surrounding area in protest as with the Cazerolazos of 2012 and in reaction to Federal Prosecutor, Alberto Nisman’s suspicious death in 2015.

More recently people protested Argentina’s long, strict Covid lockdown in the Plaza de Mayo.

In 2019 after Diego Maradona’s sudden death hundreds of thousands filled the square for his wake in the Casa Rosada.

On any given day visitors may come upon protesters or revelers in the Plaza de Mayo, a testament to the democracy Argentina’s founding fathers sought when they fought for independence from Spain.

-Rosie Hilder