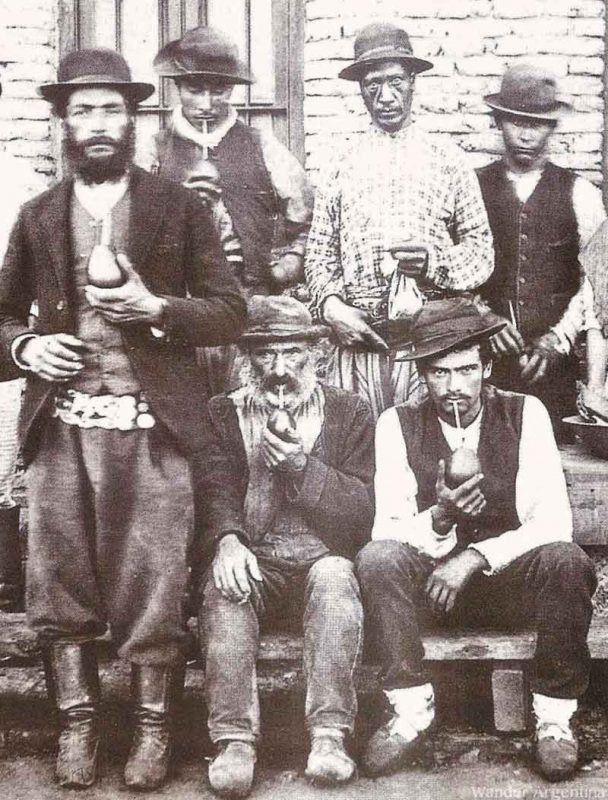

Argentina’s most traditional foods date back to the founding of the country and are eaten on its most patriotic holidays.

Argentina’s flag-waving national holidays fall in the autumn and winter months.

That means it is time for asado (grilled meats), thick stews and deep-fried snacks such as empanadas, tortas fritas and churros.

The most typical ‘national and popular’ Argentinean foods are eaten on holidays celebrating workers and the inception of Argentina.

European immigration at the end of the 19th century changed Argentine cuisine.

These popular foods are representative of the ‘creole’ culture and predate the Italian immigration wave that influenced Argentinian cuisine decades later bringing pizza, pasta and coffee.

Asado:

Asado is Argentina’s national dish and its preparation is a ritual.

Argentina is one of only a few countries that contains more cattle than people, so grilled meat is the most popular dish year round.

An asado is an event — not just a style of food preparation — and the whole occasion is a collaborative effort culminating in a carnivorous feast.

Central to the production is the asador, who lights the fire and oversees the grill, called a parilla.

Meanwhile, family and friends prepare the salads and sauces and enjoy the entrees of a picado, or meat and cheese platter. The key to a well-prepared asado is slow-cooking the meat, which is only seasoned with salt.

Next the sweetbreads (offal), chorizo (sausage) and morcilla (blood sausages) come off the fire and are served.

Finally, expect to see cuts of beef, hopefully prime cuts such as bife de chorizo.

Patriotic dates, particularly 9 de Julio (Argentina’s Independence Day), are one more excuse to get together with friends and family, heat the grill and prepare the barbecue.

Discover the Asado meat tradition with an eight-course tasting menu in Palermo, Buenos Aires.

Enjoy Argentine classic cuts of meat in a fireside dining setting.

Fire, food and the atmosphere and probably new friends! 🔥

Choripan:

The iconic choripán is embedded into Argentine culture.

A chorizo is a pork sausage, sliced in half, cooked on a grill, and slapped inside a baguette.

National holidays, soccer matches, barbecues, even political protests — none of them would be the same without the smell of choripan in the air.

The Argentine chorizo isn’t spicy like the Spanish version, but it is accompanied by sauces that add some flavor, such as fresh criolla or the (moderately) spicy chimichurri.

Gauchos (Argentine cowboys) invented the choripan in the 19th century.

Today, Choripan (or ‘chori’) is Argentina’s most popular street food and one of the idiosyncratic dishes.

There are small grills in parks and ‘chorimobiles’ (food trucks selling chorípán) at street events, transforming the typical ‘chori’ into the most popular street food.

It’s no coincidence that there are choripan stands along Buenos Aires’ waterfront where there are people taking a stroll during the day and many nightclubs.

It’s hard to resist a choripán and when the discos close down in the morning, and it’s a custom for Buenos Aires late-night partiers eat a choripan in the morning.

The chorizo sausages that choripán contains are also the first thing to come off the grill and serves as an appetizer at asados.

Locro:

Locro is an indigenous staple food that Argentinians eat every 25th of May, a tradition that has been around since Argentina’s Revolution in 1810.

On this rainy morning, people gathered outside the Cabildo (city government administrative building) in the Tucumán province in hopes of finally overcoming the Spanish monarchy.

‘Locro al paso’ (Locro on-the-go) was one of the most common dishes sold on the street at the time.

Crowds from the various political parties made a fire under the Cabildo’s overhang and cooked for everyone gathered.

The locro was delivered to legislators who were busy in long meetings.

Finally the good news arrived: Argentina was free to elect their first democratic government.

This set the tone for the beloved tradition of eating Locro during ‘Semana de Mayo’ (Week of May 18-24) and particularly on the 25th of May, when the first patriotic government was born.

This patriotic dishes’ principal ingredient is hominy, beans, vegetables and the inevitable presence of different cuts of meat and juicy chorizo.

It’s a meal meant to be shared by every family in every household on May 25, Argentina’s equivalent to America’s Thanksgiving.

Mazamorra:

Mazamorra is a porridge-like dessert that traditionally was made with the leftover hominy from locro.

The corn stew is a simple recipe of just pre-soaked white corn with water and sugar.

In the Northwestern provinces of Salta and Jujuy a related dish is called anchi and still consumed regularly, often with citrus and fruits added.

Mazamorra is a variation of the dish that was served in Cordoba and the River Plate region.

They spiffed up the leftover hominy by adding milk, vanilla and cinnamon, ingredients that made it a downright aristocratic dish at the time.

Mazamorra was said to be, ‘For the poor and old women without teeth’ and it was a favorite inexpensive dish for kids.

In the colonial era it was widely consumed and sold by women called mazamorreras out of carts to earn extra money.

Mazamorra lost its status as a ‘typical dish’ (as happened to carbonada) but many Argentines continue to eat this dessert on important national dates.

After Argentina’s European immigration waves in the 19th and 20th centuries, it’s more common to see the similar dessert, arroz con leche (rice pudding) in the River Plate region than mazamorra.

Mazamorra/Anchi is still served to kids in the Northwestern Andean regions of the country.

Guiso Carrero:

Whether you call it guisado, guiso carrero, guiso criollo or simply guiso these are different versions of the same dish.

‘Guiso’ is a traditional stew composed broth, spices, vegetables, and different cuts of meat, boiled in a pot.

Guiso was first mentioned in a Catalan recipe book in 1477.

The original recipe has been riffed on all around the world, and modified according to the customs and produce of each different country.

So, what makes Argentinian guiso different?

When long trips were made by horse carriage, typically people stopped at least twice a day to eat.

A huge black cast-iron pot that hung of the back of the carriages during travel was used to cook the stew.

It was called ‘guiso carrero,’ because of the carriage — ‘carriage stew.’

The meat is browned and combined with chopped vegetables such as onions, green peppers, corn, tomatoes, potatoes, pumpkin.

Spices can include garlic, oregano, thyme, cummin, paprika and bay leaves.

The dish was influenced by the Hispanic presence in Argentina but once the Italians landed in the country, noodles were added, to absorb the broth while in transit.

Since Argentina is a country vastly influenced by immigration from Europe, the Middle East and other Latin American countries, different elements were added to this stew through the years.

The Spanish added bell peppers, mushrooms came from Italian cuisine, and lentils from Levantine cuisine.

Guiso de lentejas is a popular dish to make at home, since lentils are one of the least expensive foods.

Today, there’s not just one recipe for ‘guiso Argentino’, and some cooks use rice instead of noodles.

Every Argentine family has its own guiso recipe, and it’s typically passed down from generation to generation.

Guiso is also enjoyed on and around patriotic holidays, and throughout the wintertime. It’s a meal so filling, you’ll need a nap after eating it.

Empanadas:

Argentinian empanadas are a popular dish you can get anywhere at any time across the country.

Even though empanadas are today known as a Spanish dish, they were first introduced by the Moors to Spain in medieval times.

This baked (or fried) turnover pastry has many types of fillings: meat, chicken, ham and cheese, vegetables and even sweet ones filled with applesauce.

Every different empanada has a different repulgue, or pastry fold, so you can identify the ingredients of each one.

Empanada are found on the table of every Argentine household during the national holidays and are eaten at lunch, merienda or dinner.

Empanadas were a popular dish during the time of the May Revolution as they were portable. They were sold on the streets as a quick snack for the ‘working man’ although back in Colonial times they were usually consumed at room temperature.

Empanadas are found in every corner of Argentina, whether it be in church charity functions, school lunch boxes or at tiny convenience stores on the pampas.

Read more about the empanada varieties of Argentina ➡:

Tortas Fritas

Tortas Fritas, which translates simply as ‘fried cakes’ are a crispy fried dough made only with water, salt, flour and lard.

Argentina’s version of Germany’s kreppel were introduced to the gauchos with the arrival of immigrants and are today enjoyed on national holidays.

Argentine school kids are taught that early in the country’s history, women in rural areas would collect rainwater so they could prepare the simple bread, which doesn’t even need yeast.

Ever since then, tortas fritas have been associated with rainy days in Argentina.

On gray, drizzly days it’s an Argentine custom to watch a movie or TV series and enjoy a big plate of tortas fritas, washed down with warm mates.

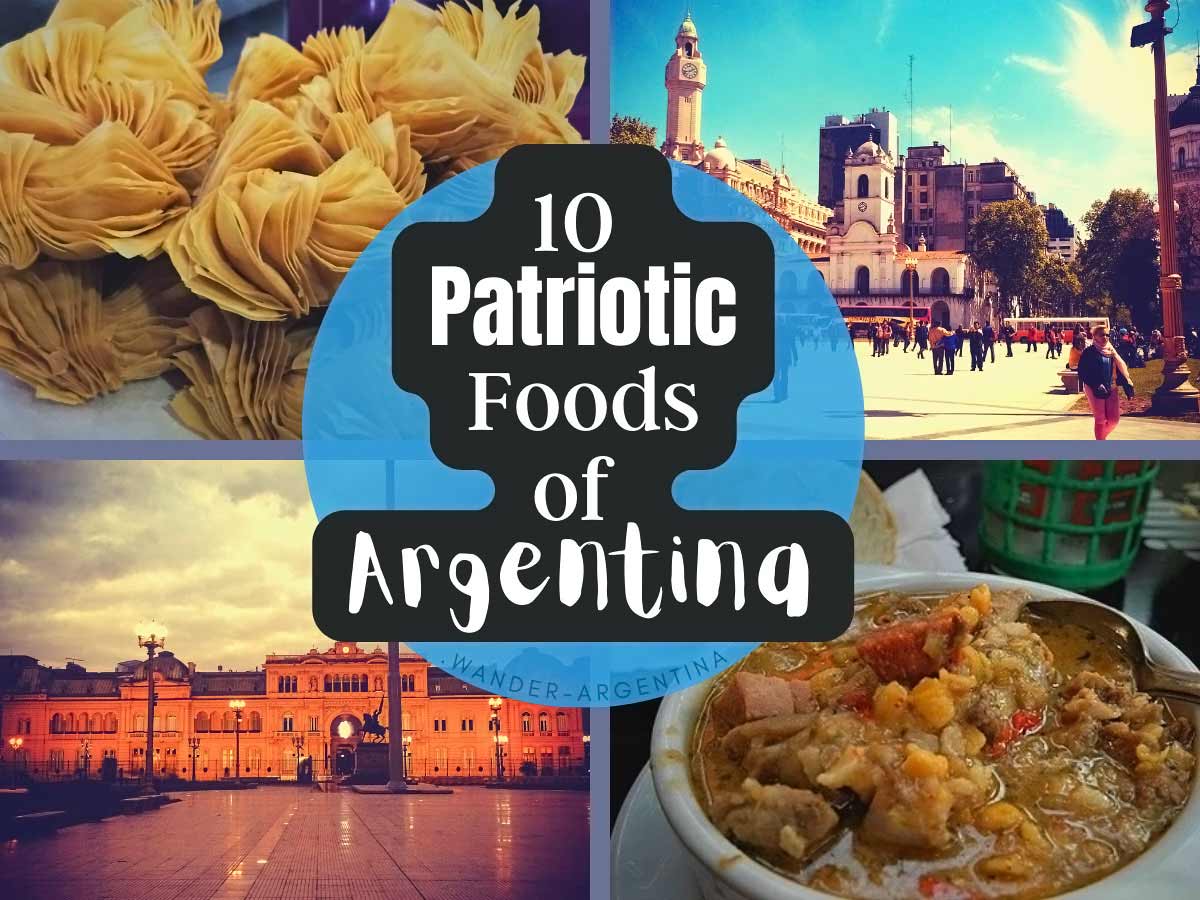

Pastelitos Criollos:

Pastelitos criollos, or simple pastelitos, are a popular crispy puff pastry, typically filled with quince jelly, sweet potato or dulce de leche.

This typical Argentine puff pastry is a crunchy, sticky treat that is obligatory on May 25 to celebrate the sweetness of Argentina’s Independence.

On Argentina’s Independence Day on May 25th, 1810 the women carried baskets on their heads brimming with these homemade pastries to share in celebration of the first national government.

Women still sell them on the street on this holiday yelling out, ‘Pastelitos calientes que queman los dientes’ (‘Hot cakes that burn your teeth’).

Patelitos are found in bakeries, convenience stores and even on the streets all year long.

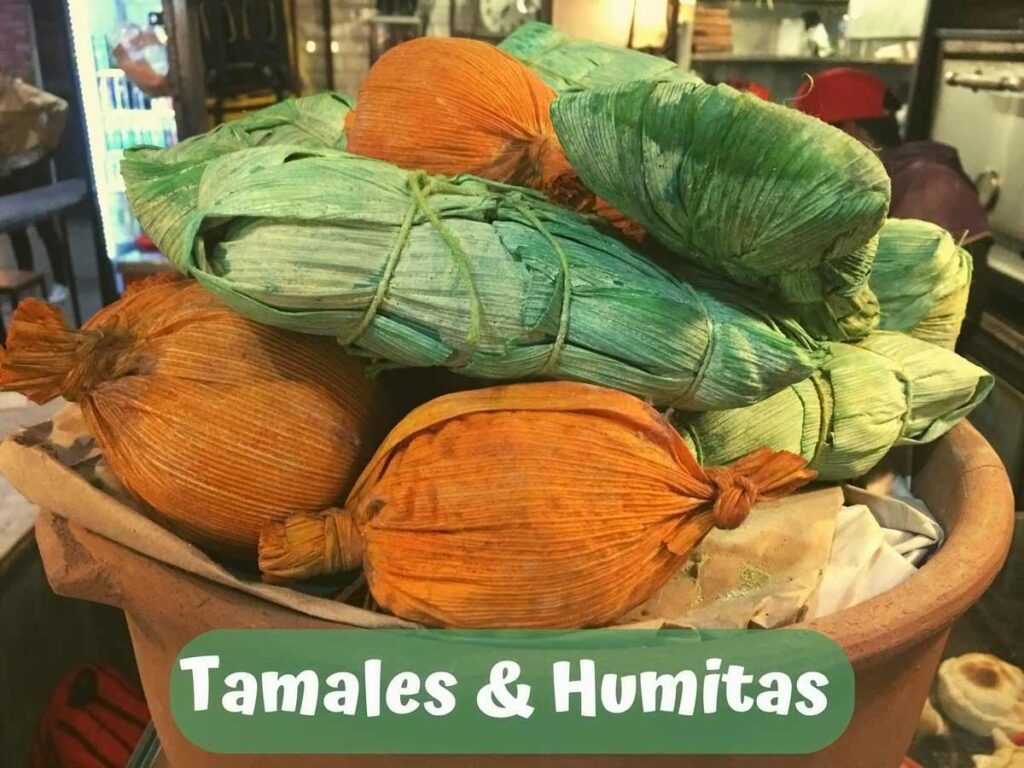

Humitas & Tamales:

These two corn-based dishes are traditionally consumed in indigenous regions in northern Argentina.

Several nations claim fame for the creation of these native Andean dishes as they were around long before the colonizers arrived. But each country has its own unique version, featuring different ingredients.

Humita is made from a maize dough of ground hominy, wrapped in its own ‘chala’ (leaves), tied with a little bow that makes it look like a present.

It’s steamed, boiled or baked or more traditionally cooked over fire or in a clay oven like the native Patagonia dish, curanto.

The Argentine version contains sautéed onions, pumpkin, tomatoes, bell pepper and spices. In some provinces such as Tucumán or Salta, fresh goat cheese is also added.

Tamales are made with corn flour steamed in corn husk, but in Argentina they are filled with minced meat, cumin and chili pepper.

This pre-Hispanic dish is still eaten daily in the north of Argentina but it is considered more exotic in other areas of the country, where it is eaten on May Revolution Day and Independence Day.

One place to find humitas and tamales in Buenos Aires is at the weekly Mataderos Country Fair.

The provinces of Tucumán and Neuquén have annual humita festivals.

Of interest to the health conscious and vegetarians, in 2021 agricultural workers organized the ‘Humita in Danger festival’ in the province of Buenos Aires to encourage sovereignty among farmers fighting against the domination of GM corn used in corned-based foods of Argentina.

Churros:

Churros are a cylindrical snack made of fried dough, covered in sugar.

They are originally from Spain, but the Argentine twist adds the unsurprising addition of a dulce de leche filling that squirts in your mouth when you bite it.

In Argentina churros are ubiquitous on the beach, at merienda (tea time), and street fairs and also on patriotic dates, to celebrate the anniversary of the May Revolution and Independence Day.

The original Spanish tradition of accompanying churros with a cup of hot chocolate for dipping lives on in Argentina.

Look for hot chocolate and churros being handed out on national holidays by soldiers and find them at classic Buenos Aires cafes, such as Cafe Tortoni.

The custom of having churros on the streets with a cup of hot chocolate was solidified during Revolution of the Park (Revolución del Parque) when the 1890 uprising led to president Juárez Celman resigning.

At home, it’s more common for provincial Argentines to eat churros with yerba mate during the afternoon siesta or teatime.

If you’re interested in Argentina’s food traditions, read about typical and sometimes strange Argentinian Christmas food ➡️ and the vast array Christmas time desserts and sweets ➡️.

or read about Argentina’s interesting culinary quirks and other typical dishes ➡️