International Women’s Day, on March 8th, is considered an important holiday in Argentina to honor women.

It’s is a day to celebrate women and their contribution to society and in recent years #M8 has evolved into an opportunity to draw attention to women’s issues.

‘Día de la Mujer’ as it’s known, is celebrated in Argentina at its most visible level through personal relationships.

Women will most likely be congratulated with ‘Feliz Día’ throughout the day by family, coworkers and friends.

Bars, restaurants and spas offer special promotions for women.

Men buy flowers or sweets for the women in their lives and make a production of doing extra chores around the house.

Recalling the holiday’s political roots in labor movements, in the last 10-15 years Women’s Day has been revived as an occasion to highlight women’s rights issues in Argentina, with demonstrations and cultural activities.

Whether a personal, political and commercial occasion, Women’s Day is a significant date in Argentina and in wider Latin America.

History of International Women’s Day

Often obscured in the contemporary narrative around International Women’s Day is that it’s a holiday deeply rooted in social labor movements.

In the over a century since it first started, the occasion has also been called, ‘International Day of Working Women’, and ‘International Day for Women’s Rights.’

Originally called ‘International Woman’s Day,’ it was first observed in the United States in 1909, when the Socialist Party of America organized a huge garment workers’ strike that took place in 1908.

The strike was led by women workers who toiled long hours in clothing factories in New York City.

They demanded safer working conditions, a shorter working day and better pay.

The women’s movement captured newspaper headlines worldwide and caught on among anarchists, socialists and women’s labor groups around the world, including Argentina.

In 1910, German feminist Clara Zetkin, suggested at the International Conference of Working Women in Copenhagen that Women’s Day should be held annually.

The measure was approved and prompted the introduction of Women’s Day around Europe in countries such as Switzerland, Germany, Austria and Denmark. Zetkin remains a popular figure among activists in Argentina.

Three years after the original garment workers’ strike in New York City, a tragedy brought more attention to the cause of women’s labor and safe working conditions.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, was a catastrophic blaze that killed 146 (123 of whom were women and girls) workers in less than 20 minutes.

Women’s activism in response to horrific tragedy helped to usher in measures for safer working conditions and less grueling hours in the United States.

In Russia, women observed their first International Women’s Day in 1913, under the motto ‘Bread and Peace’ to protest against the First World War and the oppressive tsarist regime.

After the Russian Revolution, women won the right to vote. Vladamir Lenin declared March 8th an official holiday in 1917.

In China, Women’s Day was unofficially celebrated among communist party members as far back as the 1920s. It became an official holiday when the communist party took over in 1949.

In 1975, the United Nations officially recognized March 8th as International Women’s Day and it became a global event.

How Women’s Day is Celebrated in Argentina

In Argentina, Women’s Day is a working public holiday, although some provinces such as Neuquén declared it a non-working holiday for state employees.

There are proposals to convert it into a non-working day for women nationwide.

Personal relationships and celebrating the contributions of women are traditionally the main focus of Women’s Day in Argentina.

Among couples and families, it is treated similarly to Valentine’s Day in northern countries.

Families and friends often exchange small gifts and tokens of appreciation to honor the kickass women in their lives.

Private companies and organizations celebrate the day by organizing events and activities that recognize and appreciate the contributions of women.

Foreigners with local girlfriends won’t want to overlook the significance of Women’s Day and may want to head to the Almagro flower market for a nice bouquet.

History of Women’s Movements in Argentina

In the early 20th century, women in Argentina faced challenges such as restricted participation in public life, right to vote in elections, and limited opportunities for education and work.

The origin of International Women’s Day in Latin America can be traced back to the early 20th century when women’s organizations began to emerge in various countries in the region.

Women in the Rio Plate region were organizing around the same time as their sisters in New York, just as the Victorian Era was ending.

A magazine called ‘Nosotras’ (the word ‘We Women’) was founded by María Abella, Argentina’s first self-declared feminist in 1909.

Argentina’s National Feminist Party was formed in 1911 in response to the social and political challenges faced by women, including discrimination, inequality, and lack of representation in the public sphere.

They proposed women’s suffrage, equal rights for children born out of wedlock, protections for women and children and equal educational opportunities.

Other early women’s organizations and groups in Argentina are the Center for Women Socialists, formed in 1902, the Argentine Club of Women, formed in 1921, National League of Women Freethinkers founded in 1909, and The Association for Women’s Rights, formed in 1919.

Many of the women’s groups formed in Argentina were based in the ‘culture of resistance’ with socialist and anarchist ideology.

Other women’s groups were formed by middle-class and upper-class women were less radical, but also promoted education, women’s suffrage and did charity work to support the needs of young, unmarried women with children, who often lived in poverty.

Some of the women’s rights groups in Argentina in the 20th century did not fundamentally challenge gender roles but nevertheless banded together to secure more rights for women.

Even Eva Perón, human rights campaigner and and first wife of President Juan Perón, rejected feminism despite being Argentina’s first female to hold political office.

She became the head of the Ministry of Health and established homes for single women with children.

‘Evita’ as she was affectionally known, is also credited with securing the right for women to vote in 1947.

In the 1950s and 60s, Argentine feminists were largely grounded in labor movements and the literary world.

Some took to translating feminist books from other countries to be published in Argentina.

Writer Maria Elena Walsh wrote essays on the topic but the works didn’t get as much attention as her children’s books.

Women During the Last Dictatorship

During the repressive military government of Argentina that lasted from 1976-1984, women activists were kidnapped and killed by the regime.

This is when one of Argentina’s most well-known women’s groups, the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo (Mothers of May Square) was formed.

They were mothers who protested to find their missing children who had been kidnapped and killed by the government.

Azucena Villaflor, a founder of the group whose son and daughter-in-law had been disappeared by the government, also became a victim of the murderous government.

During the brutal dictatorship some women activists and even artists, including people such as Argentine folklore superstar, Mercedes Sosa, fled the country.

Most non-activist women laid low during the last dictatorship.

Once a democratic government returned to power in Argentina in 1984, women became more outspoken about issues such as gender imbalance of household labor, sexual harassment in the workplace and lack of political representation.

Their efforts helped to legalize divorce in Argentina in 1987.

In recent years, feminist activism in Argentina has continued to evolve, with women’s organizations and feminist groups playing a key role in gaining more reproductive rights and drawing attention to violence against women.

International Women’s Day Activism

Women’s Day has been revived as a platform for women to demand greater social, economic, and political rights in recent years.

Activists say the holiday should return to its roots and be a day to commemorate, not celebrate.

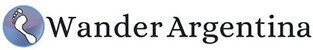

Women’s rights groups and feminists organize marches and rallies in major cities across the country, demanding equal rights and an end to domestic violence and femicide.

In 2017 Argentina’s women participated in #M8, the Women’s Strike on March 8th.

Instead of working, they held demonstrations and protests across the country to demand greater rights and representation.

Before the legalization of abortion in 2021, advocacy for reproductive health services was a significant aspect of women’s rights activism in Argentina.

In 2024, with a shift in government at the Casa Rosada, reproductive rights for women are again under threat.

International Women’s Day Activities

Art exhibits, film screenings, concerts, and theatrical performances around the country highlight the role of women in the arts.

While it’s a big date night, single women will also discover groups of women go out on Women’s Day. Restaurants and bars capitalize on the occasion to offer special deals for women.

In the Argentine capital of Buenos Aires, there are special art exhibits and events in honor of Women’s Day in places such as Sívori Museum, Technopolis and the Centro Cultural Kirchner.

Check the culture ministry’s page or local paper in your location to find Women’s Day events.

Women in Argentine Politics

Argentina had a female president as early as 1974.

‘Isabelita’ Perón

Argentina’s first female president was Isabel Martínez de Perón in 1974. The second wife of Juan Perón, she was Vice president on the Perón-Perón ticket.

She took over the office of the presidency when Juan Perón died but it was such a disastrous presidency that ‘Isabelita’ was exiled to Spain.

Her presidency ushered in a military dictatorship. Now in her ninth decade of life, she lives in Madrid.

Two-time former president and the first woman elected to the office, Cristina Kirchner now serves as vice-president.

Although a polarizing figure, she is widely viewed as the most powerful politician in the country.

Some might argue she operates as the de facto President and is the country’s first Caudilla, albeit in a contemporary form.

Two-Term President, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner or CFK, could also be characterized as a caudilla.

She served as president for two consecutive terms from 2007-2015 and was vice president from 2019-2023.

Her tenure was marked by a blend of charismatic leadership, populist policies, suspected money laundering and a deep connection with a segment of the Argentine population that saw her as the heir to the Peronist legacy led by Evita Perón.

Women’s Representation in the Argentine Congress

In Argentina, women’s political representation is stronger than in many countries.

Argentine women hold around or above 40% of the seats in the National Congress. The ‘Ley de Cupo Femenino‘(Female Quota Law) implemented in the 1990s requires women to make up at least 30% of the congress.

By contrast, in the United States women make up 26% of the Legislative Branch.

Gender parity laws are now under threat as President Milei believes it is an overreach of government powers and interferes with the principles of meritocracy.

Problems facing Women in Argentina today

Today Argentina is still a ‘machista’ (chauvinist) society although it sometimes takes a different form than in other countries and is less overt than in decades past.

Freudian psychology is still the mainstay of psychologists in the country and there is even a neighborhood in Palermo called ‘Villa Freud.’

The madonna/whore dichotomy is deeply rooted in the psyche of Argentine citizens.

Still evident in Argentina — although less than in some other Latin American countries— is the Catholic idea of ‘marianismo,’ the compliment to machismo that maintains that should be like the Virgin Mary, obedient daughters and wives, submissive to men.

Street harassment takes form in men honking their horns at women on the street or finding a way to interact in order to toss out a ‘piropo’ (flowery compliment characteristic in the River Plate region), although the practice is becoming less common.

Now that women have secured more reproductive rights, focal points of the current women’s rights movement include the following:

Household Chores & Child Rearing

As in many other countries, women still do the bulk of the housework in Argentina, even if both parents work full-time.

As traditional family units dissolve, women’s uneven burden in child rearing has grown.

While there are many involved fathers within intact families, Buenos Aires’ provincial government released a study that revealed that 70% of separated or divorced fathers in the province don’t make child support payments or otherwise help raise their children.

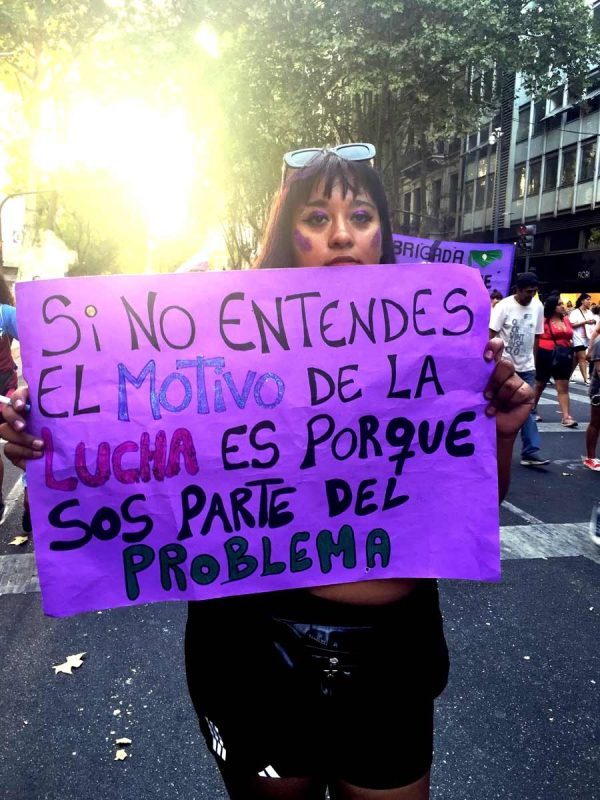

Standards of Beauty & Commodification

Argentina has a long history of sexual objectification of women, easily evidenced in its most famous music tango and on radio and TV.

Argentine society places a strong emphasis on beauty and qualification for a job may be more focused on a woman’s appearance than their work experience.

On summer television programs, there are closeups of women’s body parts on the beach with reporters asking hard-hitting questions to attractive women such as their age and marital status.

There is only one woman sports reporter for every nine men, according to a report Argentina’s Observatory of Discrimination in Radio and Television.

On network entertainment programs there are ⅓ more men than women appearing on camera.

Women on TV are frequently dressed in skimpy outfits — even for news programs — while men are dressed in typical professional attire such as suits.

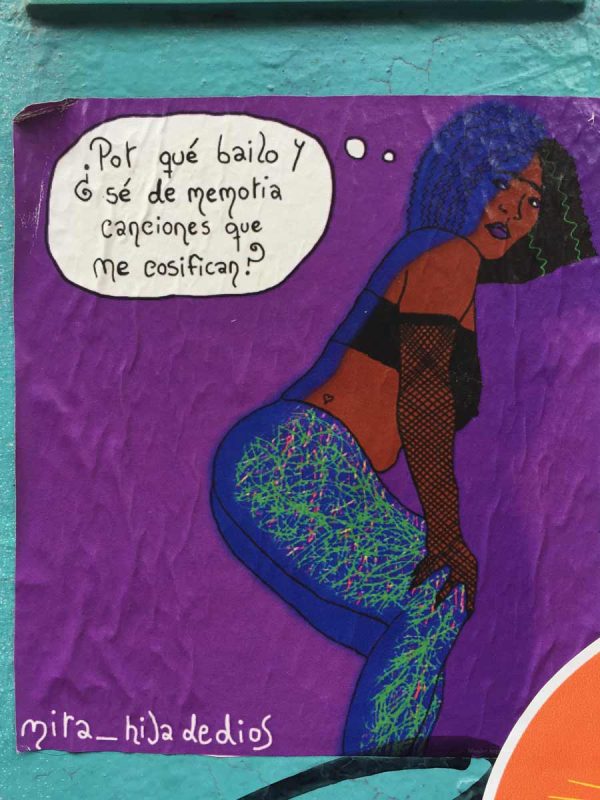

Melina Maqueda, 21 years old, attended 8M 2023 with her mom, Cristina Barreto. Maqueda carries a sign that says, “Stop marketing our vaginas.”

She says women are heavily objectified in the media and otherwise manipulated by advertisers with higher-priced products, commonly called the ‘pink tax.’

Aside from older starlets who maintain a media presence, seeing a woman who doesn’t fit into mainstream beauty standards as an anchor or host on Argentine shows is rare.

Because of the premium placed on women’s looks, extreme beauty treatments such as plastic surgery are common.

Aesthetician, Dr. Silvana Dato estimates that at least 80% of women in the wealthiest areas of Buenos Aires get regular aesthetic treatments.

The premium put on one’s appearance is so high that some private insurance plans in Argentina even include plastic surgery.

Violence Against Women — ’Ni Una Menos’ Movement

One of the most visible feminist movements in Argentina in recent years has been the ‘Ni Una Menos‘ (‘Not One Less’) movement.

It emerged in 2015 in response to the widespread problem of sex-based violence in the country.

In machista culture, men dominate their wives and children, and women are expected to be submissive.

Examples can be found in the music that is emblematic for Argentina: Tango.

Tango legend, Carlos Gardel composed a song Tortazos (Smack) that contains lyrics threatening violence toward a woman in an act of vengeance.

One of the most machista lyrics is Cacho Castaño’s, ‘si la violación es inevitable, relájate y goza‘ (if sexual assault is unavoidable, relax and enjoy).

Castaño also had a controversial 1976 song with a title that translates as, ‘If I catch you with another I’ll kill you.’

Today, women have put a new turn on tango with women dancing lead and same-sex tango pushing back on tango’s misogyny and binary approach to dance roles.

This deeply rooted machismo set the tone for Argentina’s Ni Una Menos movement, which has been credited with sparking a broader feminist awakening around Latin America.

The movement began when Chiara Páez, two months pregnant, was viciously killed by her boyfriend.

Women held protests and demonstrations across the country.

The case brought attention to the statistic that a woman is killed an average of nearly once a day in Argentina due to male violence.

Women seek changes to current laws that they say don’t provide sufficient protection to domestic abuse, stalking and trafficking victims before something terrible happens.

Buenos Aires accountant Mariana Violo brought her four-year-old daughter to the 8M demonstration to introduce her to women’s empowerment.

“I want women to have the same opportunities as men in every sector of society.”

But she says her main topic of concern is prompted by Ni Una Menos — the issue of violence against women.

“I want to feel safe when I go out on the street,” she says.

In addition to Ni Una Menos, there are other movements in Argentina working to promote women’s rights and social justice.

Argentina’s Version of #MeToo : Yo Sí Te Creo

Argentina’s equivalent to the #metoo movement is ‘Yo Sí Te Creo’ (Yes, I Believe You).

It emerged in response to the wave of accusations of sexual assault and harassment among prominent actors and politicians in Argentina.

In response to the efforts of women activists, in 2015 the statute of limitations for violence against women was extended.

Women’s Strike

In recent years Women’s Day isn’t just an occasion to celebrate women, the holiday has also helped to raise awareness of the challenges faced by women in the country.

Hundreds of thousands of Argentine women participated in the 2017 Women’s Strike, and have since had a large yearly presence on 8M.

Unrelenting protests by women for reproductive rights in Argentina made worldwide headlines for years before the legalization of abortion in 2021.

Women’s Day Detractors

The celebration of International Women’s Day in Argentina is not without controversy and has become a polarizing day in recent years.

Some critics dislike the commercialized nature of the holiday, saying it detracts from the larger struggle for women’s rights and equality.

Others argue that the day tokenizes women and reinforces traditional gender roles.

Some object to the politicization and co-opting of the day to incorporate other political issues unrelated to women.

Radical feminists and other women object to the previous Argentine government and municipalities’ incorporation of trans and non-binary individuals in events since the traditional focus of the day is on sex-based rights, such as reproductive healthcare and maternity leave.

Some Argentine men complain that women already have equal pay in the public sector and they retire five years early.

But women maintain that male dominance can take place in covert forms such as women being overlooked for promotions for rejecting unwanted advances or due to child-rearing duties.

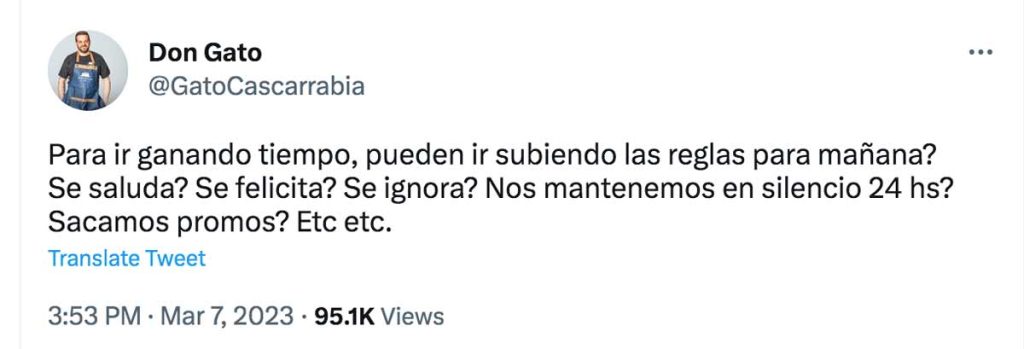

Some local men express confusion about how to celebrate the day since its renewed politicization, with one male Twitter user asking,

“What are the rules (for Women’s Day)? Do we greet you? Do we congratulate you? Is it ignored?”

The question highlights that Women’s Day is a multi-faceted holiday interpreted in a variety of ways.

It’s evolved from a Valentine’s Day-like holiday to celebrate women, to a date to remember the women who paved the way for greater equal rights, to a day to take to the streets to continue women’s fight for justice and equality.

On a personal level, Women’s Day is an occasion for small gatherings with friends and is marked by a sense of camaraderie and solidarity among women of all backgrounds.

On a commercial level, Women’s Day has become a significant market for businesses looking to capitalize on the holiday’s popularity, to the dismay of protesters.

There is the widespread sale of flowers and chocolates, as well as marketing campaigns to appeal to women consumers.

Finally, Women’s Day has been disinterred from its labor rights roots to become an opportunity for women to raise awareness about the issues that affect them most.

From domestic violence to the commodification of women, to workplace discrimination, Women’s Day is viewed as a platform to highlight women’s issues and demand change.

Women’s Rights movement and Women’s Day in Argentina have evolved and reflect the complex ways in which women’s roles in society and their issues are interpreted by different spheres of society.